Tag: ASW

18 Posts

Saab Bound for Naval Grand Slam?

Flotilla 2020 – A Strategic Acquistion

Meripuolustuspäivä 2016 – Maritime Defense Day

Squadron 2020 – Made for the Finnish Coastline

MTA 2020 – Bigger Hulls and Added Capabilities

Korean Sabre Rattling

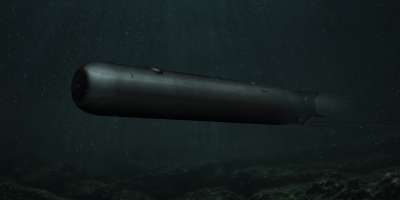

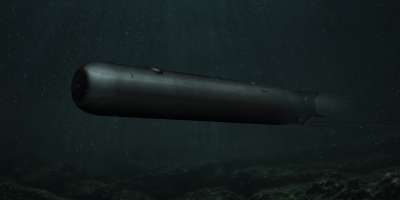

Ocean X Team and the Midget Submarine that wasn’t