Finland decided to opt for NATO-membership well over a year ago, and while the application process felt long while living it, it was indeed finished in record time (for Finland’s part, that is, we are still waiting for the Swedes, which should happen soon™). Still, it is something of a surprise that it seems we haven’t quite figured out what a number of our first few steps will be. So let us have a short discussion on those.

Finland needs to look into how you get things done inside the Alliance. Yes, it is a collection of equals. Yes, there are clearly defined workflows and processes. Yes, Finland has a good reputation. But in all fairness, in any organisation this size, there will be informal groups, there will be personal connections, there will be the ability to raise questions and issues effectively by talking to the right person. I do not get the impression we have done our homework as well as we could have since deciding to apply, and in particular it seems we have not used the Turkish delay as effectively as we could have. I also expected us to have called up Tallinn day one to pick their brains on these issues in quite some detail, but while there obviously might be things taking place behind the scenes, at the very least I feel confident to say word on the street is that has not happened to the extent I expected.

I would very much like to believe this isn’t due to the MFA (or the MoD and/or the Prime Minister’s office) falling prey to older condescending ideas about Estonia’s place in the world compared to Finland’s, ideas which we all know earlier have been quite prevalent in certain circles of the Finnish foreign policy discourse. But to be honest, I am not quite as sure of that as I would like to be. While it certainly is nice that we apparently have good direct lines to both Washington and London, having another minor ally with close to two decades of knowledge about how to get things done – in favourable and less than favourable times – inside the alliance is something that does offer the kind of unique opportunity for a jump-start to our work inside the big tent you usually just dream about.

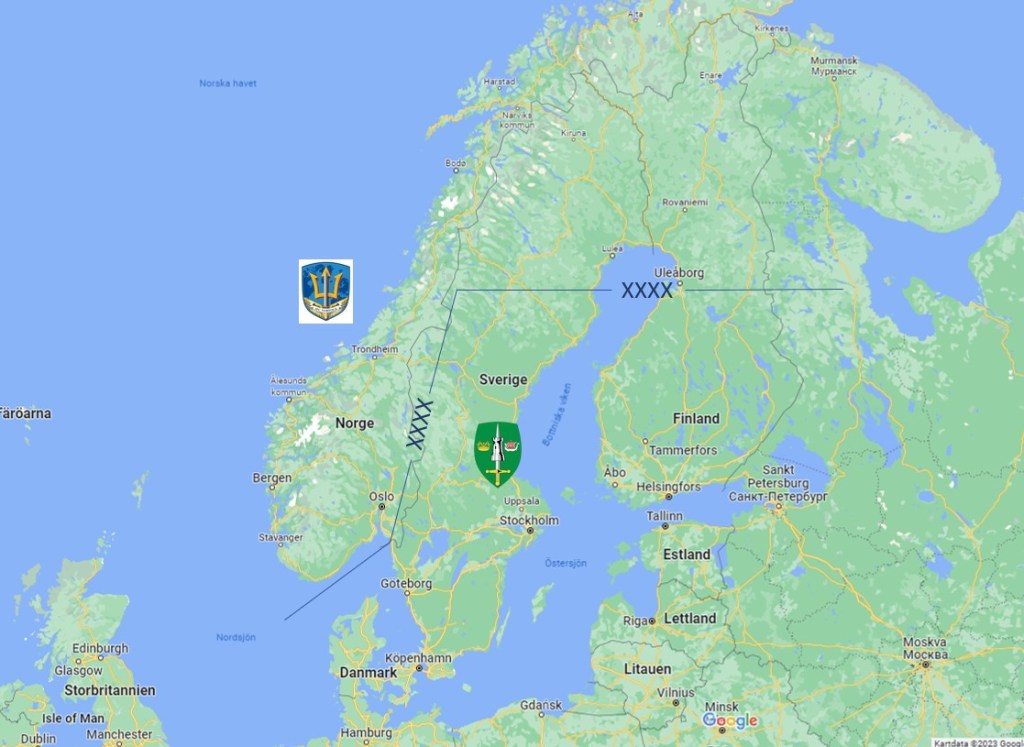

Estonia being our ally is also a key aspect to the larger discussion about which Joint Force Command to Finland need to sort under. This multi-layered and complex question can be simplified into there (currently) being two alternatives – JFC Brunssum in Belgium or JFC Norfolk in the USA. Brunssum is the default option for Northern Europe – including Estonia – and a true joint command. Norfolk is heavily oriented towards the maritime domain, as it mainly cover the Atlantic including Norway, the latter which is a key detail for Finland. Finland has expressed it as a significant priority that we should be in the same joint command as Norway (and Sweden, eventually) as Tenojoki is a poor operational border (keen readers of the blog will remember my posts about the high north being a single operational area). This is all true, but somehow skips over the fact that the Gulf of Finland is an equally poor operational border, and only someone adhering to an extremely land-centric interpretation of the word ‘joint’ could argue for a border straight through a thin 70 km wide slice of strategic terrain just because it is wet. In particular as this includes the area between the capitals and most important centres of population of two allies, as well as being a piece of terrain that is one of the most important spots on the map when it comes to the Russian economy – and by extension control of it ranks rather high among Russian national interests.

We will need to coordinate the battle of the Gulf of Finland on a daily basis. Long-range land fires are able to reach over the Gulf, and the air battle will not be bothered by a small patch of blue on the map. Crucially, the greater St Petersburg region can also be expected to be treated as one area of operations by the Russians, and while mirroring adversary command structures isn’t a proper strategy in and by itself, it is worth noting this as it will affect their operations, which we in turn will have to respond to.

The logical military answer to Finland is not either JFC Brunssum or JFC Norfolk, but both. The north is a common area with Norway and Sweden, while the south is intrinsically linked to Estonia, the Gulf of Finland, and St Petersburg. If Norfolk is expanded to be able to lead a truly joint battle, this would be the way to go, because regardless of whether the border is here, there, or on the Danube, there will be questions about how the border is coordinated. At the same time, history has seen several nations being able to successfully lead battles despite having higher command borders. And crucially, not tying it down to a country border will make it easier to shift it around if and when the battle takes part in that particular area and you want to shift the area of responsibility slightly to ensure one of the commanders is controlling the whole thing.

Again, it does feel like the JFC Norfolk argument is based around Finland’s Nordic identity, which A) is anyone really doubting that these days, and B) is of dubious military relevance to put it diplomatically. The other political argument is that tying your command structure to the 2nd Fleet gives you a stronger connection to the US, which holds some water but overlooks the significant US footprint all over the continent with both EUCOM and USAFE providing ample of US personnel in Brunssum’s area of responsibility.

Regardless of the eventual overall command structure of the Alliance and whether that is ideal from our point of view or not – a completely new Nordic-Baltic headquarters have made its appearance in the discussions as well, and would indeed be the best fit for Finland – there are other issues which could (and really, should) be addressed in the meantime. One of these is how to show directly that we are concerned with the defence of the whole alliance, rather than just trying to get in to ensure people come to our aid. In Finnish media (and including by yours truly on my social media channels) the idea about participating in Baltic Air Policing and NATO’s Enhanced Forward Presence has been raised. These thoughts were kindly but rather sternly shot down by the Estonian Minister of Defence Hanno Pevkur in an interview with Helsingin Sanomat. In short, Estonia wants more capability being brought into the region, and Finland reshuffling a company or fighter detachment inside the region does not add capability to the Northern flank.

So how should we then approach the idea of flag-waving and our interest to strengthen our bound to our allies? One alternative is – provided we can meet the NATO planning targets while rotating out a land unit – to make a contribution to the eFP, but to do it further away. Poland might certainly be an option, or Romania might happy to get some added troops considering the tense situation along their border. However, a major question is we still haven’t figured out how we treat units deployed abroad for extended rotations in a traditional homeland defence/Article 5-role as opposed to crisis management. Are we going to use the same kind of ad-hoc units staffed by volunteers undergoing a short refresher course we employ for our internationally deployed crisis management forces? That works as long as the commitment is relatively limited and of a rather general setup, but if we want to participate with something more specific – say attaching an engineering platoon to a multinational eFP-unit – recruitment most certainly might be an issue. And that brings us to something Pevkur expressed an interest in, namely taking part in the ground-based air defence rotations being made to Estonia while waiting for their Iris-T deliveries.

In theory rotating in a Finnish surface-to-air missile unit to Estonia makes perfect sense. It is cheaper to go to Estonia compared to Romania, the logistics is also markedly easier, we would be able to soak up a healthy dose of everyday Estonian defence planning and culture which wouldn’t be a bad thing. A Finnish unit placed in the Northern parts of the country would in reality also take part in the air defence of Finland (again, when discussing the air defence of Helsinki the battlefield doesn’t magically stop at the edge of our economic exclusive zone). The problem is we don’t really have a suitable solution in our toolbox for how to stand up a highly-specialised unit and deploy it abroad for four months. This of course might be the catalyst needed for us to work out that solution – we will probably need it sooner or later – but for the time being we don’t yet have it available.

So recognising that close cooperation with the Estonians is valuable (think FISE, but us being actual allies), what could we do under the current structure? My suggestion is that we launch a high-low mix of integrating individuals or squad-sized teams into Estonian units. For the ‘high’-part, let’s call major general Palm and ask if he would like a Finnish staff officer or two in his headquarters for the Estonian Division, obviously on the Finnish payroll as they are serving in our defence forces. The Estonian Division is the highest land unit in the structure of the EDF, and while the core is made up of two Estonian brigades and Estonian supporting units, the integration of additional allied units is a key part of the concept. We already have a concept for stationing officers abroad for a few years at a time and does so in a number of roles (including in direct NATO-roles). This would provide a true win-win scenario in offering people who are relatively easy for the Estonians to integrate culturally into their force, they would be doing real and useful work, while at the same time offering Finnish officers the ability to practice their trade in a standing operational divisional headquarters (something we lack), while also getting to know how our ally on our right flank thinks and fights.

For the ‘low’-part of the mix, what we are able to offer is to identify individual roles where we already train conscripts, and where the roles are such that an integrated individual soldier in an Estonian unit can make a difference. An example of this kind of specialised roles are Joint Terminal Attack Controllers (JTAC), which not only is a key force multiplier for any unit getting one attached, but also a role which is highly standardised within NATO to ensure that they are able to operate with different air and land assets for both fire missions as well as for deconflicting the airspace – a role only growing in importance with the larger number of drones on the modern battlefield. With Finland already having years of experience training conscripts to support NATO-qualified JTACs as part of their Joint Fire Support Teams, the Finnish Defence Forces can hire Joint Fire Support Teams as these are transitioning to the reserve (or hire from the reserve if need be) and allocate them with a JTAC. The deal would be that FDF offer them set-term contracts for say 12 months, which they serve in Estonia in designated units where the Estonian Defence Forces have identified a need for more fire controllers. There obviously are questions that need to be worked out – if they are dispersed out among parent units it may for example be best to serve in Estonian uniforms with Finnish markings and with FDF mission equipment – and someone from the MoD need to call their Estonian colleagues to ask whether this in fact is something the EDF would appreciate. However, this may provide a relatively simple way of having Finnish soldiers serve in Estonia, providing real military value to the EDF while at the same time bringing tangible training benefits in their role within the wartime FDF organisation, a position to which they revert once their contract in Estonia is up. Finding a handfull of 20 year olds who would be ready to do a year in Estonia is also likely an easier prospect than being able to find 30-year old specialists in large enough numbers to man an air-defence unit.

But as a final proposal, to work out these details, I propose a suitable level visit with a naval vessel. An appropriate minister – the prime minister, foreign minister, or minister of defence – together with a suitable number of generals and admirals board a naval vessel and head over to the neighbouring capital for a nice photo shoot and a opportunities to nail down the details of what we are going to do and how. The image of FNS Hämeenmaa pulling into the port of Tallinn or EML Admiral Cowan mooring at the Helsinki market square – or alternatively FNS Hamina/EML Raju if you want a sportier look – will send a significantly more powerful message compared to them flying or taking the ferry, reminding friend and foe alike of not only Finnish-Estonian friendship, joint operational planning for the Gulf of Finland, and underscoring the geographic closeness. The ability to combine this kind of strategic messaging with useful meetings that anyhow will have to take place is an excellent example of low-hanging fruit.

Finnish Defence Forces does not train conscript JTACs.

Indeed, it’s the rest of the JFST that is made up of conscripts. Now corrected.

Good article. I have been writing and lecturing about this for at least the last 5 years. I have to say that your ideas mirror mine and coming from you are likely to have more effect. The staff officer idea is not just a good plan but is VITAL and must happen. One must also go to Latvia. Your boundary argument holds true here as well. Exchange is the strongest way to deliver trust and high quality communication. The same must happen in reverse and Finland must accept an Estonian and Latvian officer fully into the system.

I dont see how vital it is to have FDF general staff oficers daily present in an EDF divisional staff?

Or giving full access in to the FDF general staff,who does that?

Otherwise I agree that especially the air and naval forces need to be fully integrated to cover the dual capitals, Gulf of Finland and the Northern Baltic Sea LOC to both countries.

The main Finnish contribution for the land forces should be the joint LRPF capability of the FDF.

SOF have the most potential for joint operations from the land component.

If EDF wants to form coastal infantry units that would open a lot of opportunities..

Nice article! Well thought out concrete ideas forward with NATO integration.

About the question about the boundary between two commands, it is going to be interesting to see, how it resolves itself.

Cheers!

From the strategic level, the location of troops should be focused on where the threat is, not national or even regional borders (no question you need to keep troops for border control.

Finland’s most flexible entity is the Air Force. With the F-35 that is a natural to deploy in sections (like 4 aircraft at a time)

If you can’t carver out a Baltic Command zone, then the nearest HQ is better, proximity does make a difference.

Regiment or Brigade level deployments would make sense as that is the level that would be required. Deployed to any of Estonia/Latvia/Lithuania would allow some other NATO shifting as well as being close enough to Finland to establish a personal rotation home.

Clearly Russia has established it can’t even handle one battle front and future friction/conflict would almost certainly be Poland on down through Bulgaria. If in the remote possibility Finland was threatened NATO would beef up there (with huge bonus of defending Finland , Sweden and Norway). If Russia in another fit of stupidity focused on Finland, that threat would be seen a long way in advance due to what would have to be moved into the region.

Or to put it simply, Finland should be working towards being expeditionary.

For my own sake I really hope you are wrong and actually Finland with its vast and uninhabited spaces will become the next target of opportunity for Russians. They clearly must have developed a dislike now for fights for every building and every road crossing. On the other hand, they have been building equipment for the extreme conditions for a long time, unlike most of NATO, which spent years in various deserts as of lately.

There is always some goal involved even if its a seriously bad one.

I do not see anything in a Finish, Swedish or Norwegian direction. Finland is no longer a buffer state so even neutrality can’t be achieved. If it comes it will be South of the Baltic

Nice article again… I kind of think that a few years from now there will be a Baltic command group, as both the land and sea aspects differ greatly from the original concepts for Norfolk. If that happens Norway will have two important roles: defend the north Atlantic + Support the Baltic/Finland/Lapland. It will be interesting how they split those responsibilities. Final thought, if there is a Baltic command it will be fun politics and pragmatics that will decide its’ location

With the current alignment (Baltic is controlled to the point Russia can’t co anything there) Norway can dedicate its Navy to the Atlantic and at least part of its Air Force and Army to the Baltic region. It does make sense to have a seperate Norway/Sweden/Finland command and decisions on sending troops elsewhere in NATO based on the threat.