It is not often you get the opportunity to visit a warship at sea, and rarer still to get to do so on a first-of-class that hasn’t even been commissioned into service yet. So when offered the opportunity to embark the Marine National’s Amiral Ronarc’h for a day of sea trials off the coast of Brittany, I was quick to accept the invitation.

The Amiral Ronarc’h is the leadship of the FDI-frigates, or the Frégate de défense et d’intervention as the full French designation goes. These 4,600 ton vessels follow on the heels of the 6,000 ton FREMM-class frigates, and in particular the ASW-optimised Aquitaine-subclass. The French FREMM programme has seen significant cuts in numbers compared to the originally envisioned 17 vessels, as the navy eventually ended up with six ASW-roled Aquitaines and the further two air defence optimised Alsace and Lorraine. While this cut was rather dramatic, the situation wasn’t as bad as it might look like at first glance. Of the eighteen vessels to be replaced, nine where the D’Estienne d’Orves-class avisos, which are light corvettes of rather limited combat capability, and a decision to upgrade and extend the lifespan of three of the five La Fayette-class light stealth frigates together with a decision to procure a new class of OPVs (the Patrouilleurs Hauturiers-programme) which will enter service in a few years largely took part of the lower end of the spectrum. That, however, left a gap on the sub-hunting end of the spectrum, as the other nine vessels to be replaced were of the Tourville- and Georges Leygues-classes (the third Tourville, the Duguay-Trouin, having already left the fleet). Submarine-hunting is tricky business in a lot of ways, but one thing that is particularly true is the need to be on location to be able to handle the mission, and as such the number of hulls matter. And going from nine (of an original ten) large ASW-vessels to six would have meant cutting a third of the force, something the Marine National was simply not having.

Enter the FDI, a smaller and thereby cheaper ship, which could not only make up the missing numbers, but with five vessels on order the nine older frigates would be replaced by eleven modern ones (six FREMM and five FDI), covering also for the upgraded La Fayettes when they bow out. But while it would be easy to look at this and conclude that France has opted for a high/low-mix of frigates and corvettes, what the navy in fact did was ask for a second class they would be able to use interchangeably with the FREMM, sporting the same (or better) combat capability, just in a smaller package.

I would have liked to be able to have a seat in the corner and listen to the reaction of the engineers when they got that technical specification.

As a side-note: This is also where Naval Group points out that of course the FDI wasn’t a candidate for the Australian Tier 2 Frigate-programme (aka SEA 3000), as it isn’t a Tier 2-warship, but a full-on Tier 1 combatant, and this decision has nothing to do with any fallout from the AUKUS-debacle. Your mileage may vary, but if you compare the stats to those of the Upgraded Mogami-class on offer, I’m not sure that is the whole truth…

Anyway, the key part of this was that the FDI needed to be a true ASW-frigate able to operate in any location where France might want to project its power – in other words from the North Atlantic to the South Pacific – with a true multirole capability to back it up.

That means anti-air warfare capability including the ability to counter the whole range of targets from drones to ballistic missiles. For the ASW-role, shipmounted torpedo tubes, the CAPTAS 4 towed sonar system, and an NH90-class helicopter were needed, and for a land-attack capability the ability to fire cruise missiles was also included. Add to this eight heavy anti-ship missiles, a 76 mm deck gun, a top speed of no less than 27 knots, and signature reduction (as all French frigates since the La Fayettes), and you have quite the package to fit into the smaller hull.

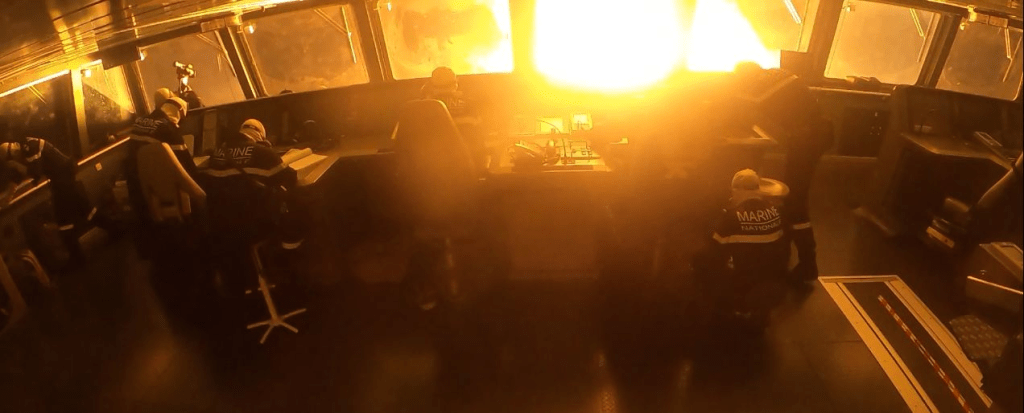

And for the FREMM, that combat capability isn’t just some paper specification either. The most widely reported operations in recent times are the deployments in the Red Sea to protect merchant shipping from Houthi attacks, and has seen the French FREMMs shoot down drones and missiles using the whole spectrum of responses – from helicopter door-gunners taking down low-flying drones with machine gun fire, via the 76 mm deck gun, all the way to the crowning achievement of Alsace bringing down three ballistic missiles, reportedly with a salvo of just three Aster 30 long-range air-defence missiles. A notable detail is that the FREMM with their fully-European air-defence setup of Thales radars, Naval Group’s in-house SETIS combat-management system, and MBDA Aster missiles apparently did not report any major issues. This is in stark contrast to the German and Danish frigates which employed a mix of US and European systems – with the German Hessen having two SM-2 missiles fail after launch (ironically thereby avoiding a friendly-fire incident as the target was a US MQ-9 Reaper drone) and the Danish Iver Huitfeldt seeing issues with their ESSM missiles leading to the system being unavailable for 30 minutes during an engagement, and a significant number of 76 mm rounds exploding prematurely.

Another weapon used in anger by the FREMMs is the MdCN (Missile de Croisière Naval), which in essence is the naval cruise missile cousin of the Storm Shadow/SCALP-EG. This weapon was used in the strikes on the Him Shinsar chemical weapons storage facility in Syria back in 2018, which saw the target wiped out after a barrage of 9 TLAM, 8 Storm Shadow, 2 SCALP EG, and 3 MdCN – the last three of which was fired by a FREMM (likely Aquitaine).

However, while the Red Sea operations are notable for the full spectrum of threats encountered and the fact that they include exchanging live fire with the enemy, a far larger part of their career the FREMMs have spent facing off with the Russian Northern Fleet and their submarines. With France relying heavily on trade routes over the Atlantic connecting the country to the rest of the world, being able to keep their shipping safe in times of war would require being able to convince shipping owners and operators that there is no significant submarine threat – and the easiest way of which doing it is ensuring that there are no submarines in the waters in question. At the same time, keeping the Russian nuclear submarines – in particular their SSNs – under watch is also of crucial importance to the French nuclear deterrent, which is heavily reliant on what usually is a single or a pair of the four available Triomphant-class ballistic missile submarines that are at sea at any given time, each carrying their share of the 240 nuclear warheads France has available for their M51 ballistic missiles. As such, there is a strong connection between the anti-submarine operations in the North Atlantic and the nuclear deterrent, meaning it is to some extent kept out of the spotlight on purpose.

But sometimes it does come to the surface.

Such as when the US 6th Fleet keep handing out their “Hook’Em” awards to Marine Nationale FREMM-class frigates. The quarterly award goes “to a unit supporting C6F which has demonstrated superior ASW readiness, proficiency, and operational impact”, and while USN units obviously dominate, the French have an impressive amount of them as well, starting with Bretagne and Auvergne bagging the award following them supporting two-carrier operations with USS Dwight D. Eisenhower and Charles De Gaulle in March 2020. This was followed by Provence and Languedoc taking home their awards following operations in the Mediterranean in the fall of 2021, and in early 2023 it was the time of the whole Task Force 470 when Vice Admiral Boidevezi’s four frigates – Aurvergne, Bretagne, Languedoc, and Provence – scored the award for their deployments in the Mediterranean the year before. Note the final three words of the award criteria: “and operational impact”. It doesn’t help you to excel at exercises, you need to actually do something useful for forces that are deployed out on operation.

Another time you get to hear about the topic is when you get to spend nine and a half hours aboard the French Navy’s newest multirole frigate, guided by Naval Group’s Business development senior manager for surface ships and systems, Yonec Fihey, former Naval officer, former FREMM-class commanding officer, and long-term submarine hunter. Outside of those in active service, he probably ranks among those with the deepest understanding of French anti-submarine doctrine and processes, and having him explain the design choices and concepts of operations of France’s newest frigate was invaluable.

As such, for the next few days, we are looking at a series of posts here on the blog which will look at the newest and most modern European frigate currently sailing under its own power.

Comments are closed.