As mentioned earlier, I had the privilege of being guided by Yonec Fihey, who spent the better part of his career hunting Russian submarines – both from the air and from the surface. As such, he was more than happy to explain the general ins and outs of how modern subhunting looks.

The basic geography and strategic goals haven’t changed since the Cold War. The key issue is still that Russian submarines based in the High North wants to come out into the Atlantic where they can hunt for high-value targets – the biggest prizes of which would be the ballistic missile submarines of the US Navy, the Royal Navy, and Marine National, as well as the large carriers which are crucial for NATO’s air and sea power. To stop this, NATO tries to find the submarines when they pass through the Greenland-Iceland-UK gap, or better yet while they are still approaching it through the Norwegian Sea.

What has changed is the opposition. The current fleet of Russian submarines is centered around a core of Project 971 Akula, with a single Project 945 Sierra reportedly still being active, as well as the new Project 885 Yasen (Graney) boats coming into service (you can get into a debate about whether the Yasen is an SSN or SSGN, in either case it’s a mean beast). And these boats are considerably more silent than their earlier counterparts. And that means that to be able to track them, you need a combination of a whole host of different capabilities.

This starts with the SSNs of the US, British, and French navies, who patrol spots where “other” means have indicated a submarine is likely to pass. What exactly these other means are was left open to imagination, but they likely constitute a combination of things such as bottom-mounted sensors, intelligence gathering using space-based and other systems to indicate a submarine leaving port, as well as the whole range of -INTs (HUMINT, COMINT, SIGINT, cyber, …), and so forth.

Once the NATO SSN has spotted the Russian submarine on passive sensors, it tries its best to stay with the contact. Unfortunately, the Russians who knows the SSN-patrols in the area is the first chain to get past has an ace up their sleeves, and regularly choose to do long sprints at high speeds – up to 28-31 knots – which they maintain four up to 24 hours to try and shake the NATO boats. The reason this works is not so much that NATO’s SSNs would be significantly slower – even the French Suffren which is generally thought of as being a bit slower than the British Astute and the US Virigina is quoted in open sources as doing 25 knots, with the two other reportedly capable of 30+ knots – as it is about the tactical and strategic scenario:

The Russian submarine would obviously prefer not to be spotted, but it knows it is transiting through waters infested by adversaries looking for it. The primary purpose of this stage of the trip is to reach the open waters, where it can hide, and then start doing its shenanigans.

The NATO submarine would prefer that it doesn’t lose the target it is tracking, but keeping itself hidden has a value in itself, as this particular target is just a single task during a longer patrol.

As such, the NATO submarine does not want to give its position away by sprinting and causing a lot of sound. In addition, the passive sensors of the submarine works significantly better at slower speeds than when at 25+ knots, meaning to some extent it would be rushing blindly after the other submarine.

So what happens, is that the NATO submarine once the Russian start running, approaches the surface, and sends out a contact report, before once again disappearing under the waves of the cold sea. At this stage, NATO needs someone who can quickly get to the location of the last reported position, detect a sprinting submarine, and stay with it while it is sprinting.

Enter the maritime patrol aircraft.

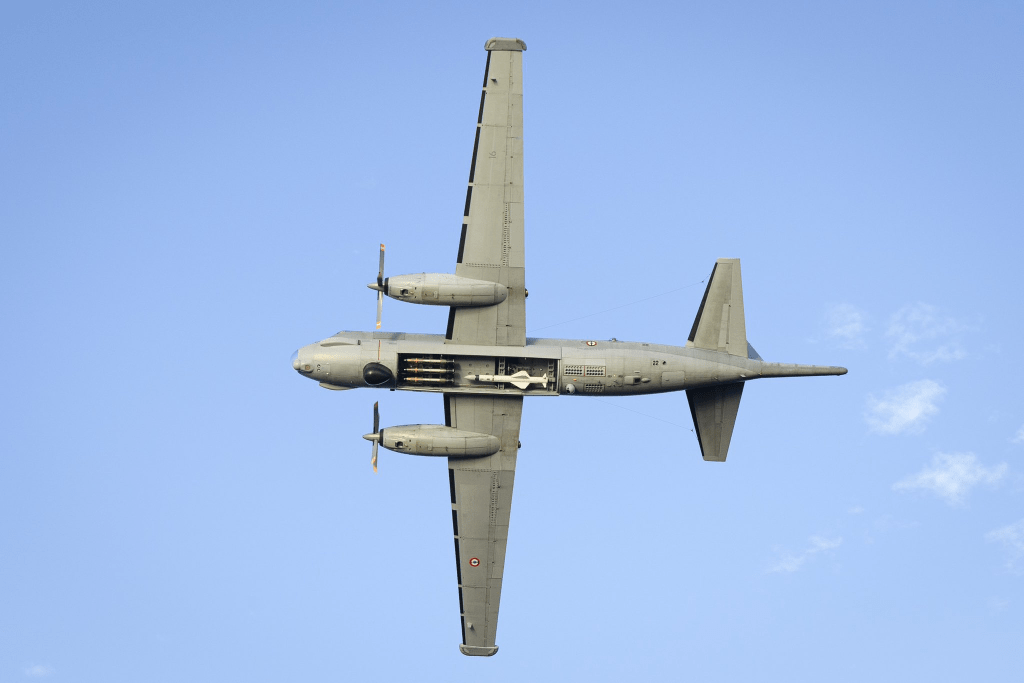

The majority of the countries involved have received or ordered the P-8 Poseidon – a converted Boeing 737 – as their primary platform while the French still relies on the classic Bréguet Br.1150 Atlantique, which in its upgraded ATL2-form still is able to provide useful service (probably, likely, maybe to be replaced by the Airbus A321MPA). These aircraft will quickly get on station, drop active and passive sonobuoys, and start tracking the target. In particular sprinting submarines present good targets for them, as the sound and disturbances in the water provide strong signatures to home in on. However, once the submarine drops its speed, the signatures get a lot smaller, including the echo from the relatively weak active sonobuoys (as these are seriously size-restricted and made on a budget that allows them to be dispensable).

However, at this stage of the hunt, the star of this series of blog posts should finally have had time to enter the stage.

The ASW frigate might not be as fast as the maritime patrol aircraft, or as silent as the the submarine, but it is fast enough to keep up with a sprinting SSN (hence the requirement for at least 27 knots top speed), has the endurance to stay with the target for a long time, and has sensors that are much better and more versatile than sonobuoys. Add to this the integrated helicopter, with its even higher speed, sonobuoys, dipping sonar, and torpedoes, and you have an extremely efficient package.

This is the concept of operations around which the FDI is designed, as it is easier to design a true ASW-frigate from the ground up, and then add the anti-air warfare capabilities and anti-ship capabilities on top of that, rather than the other way around. This comes from the need for an extremely silent vessel, in part to delay the submarine detecting the frigate as much as possible, but also to ensure that the ship-mounted sensors work as well as possible.

Much has been made about the propulsion choice of the FDI. The FDI stands out among the European ASW-frigates currently on order in having a pure diesel-drive (or combined diesel and diesel, to be precise, with two 8,000 kW MTU diesels working in pairs driving each of the two shafts), something the French have strong views on. To begin with, the changed face of ASW has meant that if you anyhow is going to spend time cruising at high speeds, the difference in sound between a combined diesel and diesel-electric or combined diesel and gas turbine electric drive is starting to even out. At the same time, the gas turbine will always suffer from higher fuel consumption. And in a game where endurance is king, fuel consumption is a serious question.

Another key aspect of the diesel-drive is the care taken to ensure that the four engines producing a healthy 32 MW (as well as any other working systems) aren’t transmitting sound into the hull. This includes the classic dampening mounts of engines and gensets, but also isolating piping from the hull to ensure there is no vibrations carried over from pumps and machinery via the pipes to the hull, or any resonance that might develop.

Acoustic signature management is hard, so it is worth noting that Naval Group is also the company responsible for France’s nuclear submarines, including the nuclear leg of the underwater deterrent in the form of the current Triomphant-class SSBN and the future SNLE 3G-class currently being built. And in a somewhat unusual setup, Naval Group is besides a shipyard also an established equipment and systems supplier. Combined, this means that the diesels are connected through in-house gear-boxes, with the whole shaftline being designed by the company based on their experience of making things for the submarine force where silence is the difference between life and death – and to ensure the ultimate deterrent of the state.

Whether the trade-off in simplicity and endurance is worth it in noise-levels (in particular at low speed) is the kind of stuff the internet will spend the next decade arguing about, but the pragmatic French design certainly has a case for it. And at the end of the day there is some truth to the blunt statement that no surface vessel can be sure of acoustic superiority and first detection over a submarine. The simple truth is that you need a design that is optimised for not just all-out silence, but for being as efficient as possible throughout the whole mission, conducted in accordance with their concept of operations.

The key sensor for the FDI-frigate is the Thales CAPTAS-4 Compact, an active very-low frequency towed array. The CAPTAS-4 is a highly regarded system, including being employed by the FREMM-frigates of various countries (including the future US Constellation-class), as well as the British Type 23 and future Type 26-class ASW-frigates (as the Sonar 2087). The CAPTAS-4 Compact is a smaller and newer version, making it possible to mount the two-part system at a vessel the size of the Amiral Ronarc’h, something that is unique for a 1-2 kHz array. There are, however, also some minor changes – largely down to a more modern coating – meaning that the CAPATAS-4 Compact reportedly is just a bit better than the baseline CAPTAS-4/Sonar 2087 at detecting targets, something that the team behind the FDI is rather happy about. In either case, the system is extremely capable even in its baseline form, and the FDI is able to use the system at up to 25 knots and in sea states 5 to 6 (corresponding to “rough” and “very rough” seas) – meaning this is also the design parameters used for the vessel as a whole, with all systems and weapons – including helicopter operations – being expected to perform up to at the very least the upper boundaries of sea state 5. After you enter sea state 6, you will have “some constraints”, though the ship will certainly still be operational. Compared to older designs pre-FREMM where already sea state 4 started to cause issues, this is a significant step forward, and ensures that the subs will continue to be hunted more days of the year than otherwise would have been the case – in particular in the harsh conditions of the North Atlantic.

The CAPTAS-4 is able to operate both in active or in passive mode, though as Fihey explains, the passive capability need a relatively slow speed to operate effectively, and is of somewhat limited use against modern submarines, due to them being both more silent and generally operating at higher speeds compared to the Cold War classics.

“Against a Victor III, why not” – Fihey on the possibility of using passive towed arrays for submarine detection

The CAPTAS-4 also sport a torpedo alert function, as does the bow-mounted sonar. This is the Thales BlueHunter (KINGKLIP Mk2), a smaller version of the BlueMaster (UMS 4110) fitted to the FREMM. It is a low-frequency design, also sporting both passive and active modes, as well as torpedo detection. While one of the major benefits of the CAPTAS-4 is the ease and speed of deployment, there is still the marked difference of the bow-mounted sonar literally being in the water 24/7, while the towed variable depth sonar needs to be deployed.

Having found the submarine, the FDI carries torpedo-launchers on both sides, with either two twin or two triple launchers being mounted, and this is where the French noted that they did find the decision by the Royal Navy not to have ship-mounted torpedoes on their Type 26 ASW-frigate somewhat strange. It has to be said that asking why an ASW-frigate doesn’t have torpedo-launchers is somewhat like asking why an officer doesn’t have his pistol – the weapon is a poor offensive aid, and you would be outgunned against your likely opponent, but the day you suddenly find yourself face-to-face with the enemy, you really want something able to shoot with for self-defence. In the same way, a submarine would also have both a torpedo with a longer range, as well as likely the better situational picture regarding where exactly the frigate is. But, ruling out that you ever would face a situation where the submarine is close enough for a quick-draw torpedo-shot feels like underestimating the chaos of war. And who knows, the CANTO acoustic decoys have a quite good reputation, including scoring a number of export successes, so maybe in a real-world situation you are able to avoid incoming fire to give yourself the possibility of sprinting into range to fire back. If so, having something to fire with does help.

The CANTO is by the way interesting in that a salvo is just two decoys, in practice giving it a greater depth of magazine for a given number of decoys compared to certain other systems.

However, perhaps the most important sub-hunting asset of the frigate is its organic helicopter. The FDI has two hangar-doors, as the 700-kg class UAS has its own door and parking space on the port side of the hangar, while the centre of the hangar is reserved for a single 11-ton class helicopter. On the French vessels, this will be the NH90 NFH Caïman, while for the Greek this will be the MH-60R Seahawk. In case Norway opts for the FDI, it can almost certainly be expected that it would be the latter as well. The spacy hangar is equipped with all the equipment needed to perform maintenance and overhauls of the helicopter, including with an overhead crane able to change engines or rotor blades. The helicopter deck handling system is, unsurprisingly, yet another in-house product, and has been exported to a number of international customers, including the Netherlands for their frigates.

The value of the helicopter is that it is able to cover significant areas, and either drop sonobuoys – which can be read, controlled, and exploited from either the ship or from the helicopter – or use its dipping sonar to look for unwanted contacts. An interesting detail here is that Thales has long been the leader when it comes to dipping sonars with the FLASH-series, used by a number of different countries under different designations (including the ALFS in US service, the Flash-S/Sonar 234 in Swedish service tailored for littorals, and the helicopters of Germany, France, the UK, Italy, Poland, and so forth). Last year France then announced that their new SonoFlash buoy based on technology from the dipping sonar will enter low-rate initial production, giving a truly European high-end active/passive sonobuoy available at a time when the “Made in Europe”-sticker suddenly has become a lot more interesting.

The helicopter is also significantly more unpredictable and hard to counter for submarines, and can safely spend significant time looking for the target before eventually being sure enough about what and where it is that it will go in for the kill with an air-dropped torpedo. The torpedo-storage room on the FDI is common for the helicopter and the ship, and is situated next to the hangar, allowing for easy transfer both to the helicopter and to the ship-mounted tubes. The Marine Nationale will use the MU90 for both helicopter- and ship-launches, while the Hellenic Navy will also have the MU90 for shipboard use, but will employ their US torpedoes (Mk 46 for the time being, likely to be upgrade to Mk 54) from the MH-60R.

The complete helicopter detachment in French service is 14, including both flying and ship-based personnel, and the ideal is that a single helicopter with crew is attached to a vessel for a longer period, 2-3 years being the stated aim. In practice this has not always proved possible, but when it does it aids with the ‘teambuilding’, for the lack of a better term. As mentioned, a high priority has been placed on the integration of the aviation component within the ship, with the aviation function having their own room in the CIC, and all the other facilities needed. Having the UAS and helicopter spaces next to each other in the same open room but with individual doors is also seen as a significant step, as it enables the operation of one without first moving the other out of the way, while at the same time ensuring maintainers and other people working on one platform can see what they are up to on the other one.

A key detail about the helideck is that while the hangar ‘only’ fits an 11-ton helicopter, the deck is rated for 15-ton machines, such as the AW101. This is of interest when operating in the North Atlantic, where the AW101 is flying both from British vessels as the Merlin HM2 ASW-helicopter, and from Norwegian and Danish bases in the search-and-rescue role. The deck is also planned for replenishment by air (VERTREP), and has a straight route on the same deck level to all food storage as well as a designated forklift route for both food and munitions, allowing anything landed on the helideck to be ferried by forklift and pallet to the appropriate storages. There is also an almost direct route to medical facilities from the helideck, though in this case you do have to travel down one deck, something that is done on a set of stairs that are significantly less steep than the rest of the stairs on the vessel, to aid with the carriage of stretchers.

But, while all shipyards try and set their vessels up for success in every imaginable way possible, sometimes things do go poorly, and you will have to deal with holes that weren’t there when you bought the thing. That is what we are discussing tomorrow.

Comments are closed.