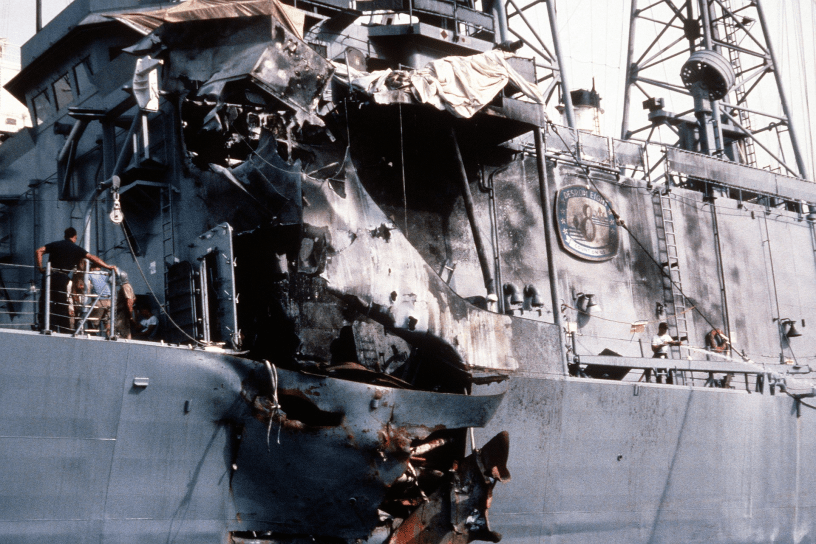

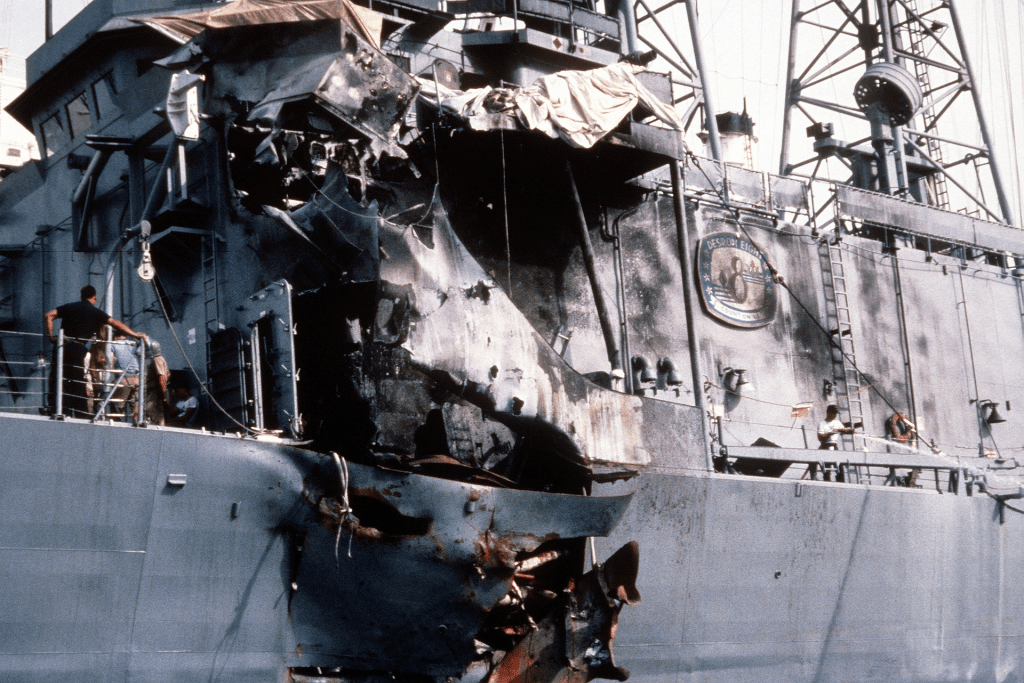

The Falklands War and the total hull loss of the KNM Helge Ingstad.

Those were two topics that were mentioned time and again while we were walking through the ship. Losses of modern major warships are fortunately quite rare, and these provide some of the most studied cases of what happens when things go wrong aboard a warship, and how effective the actions taken to save the vessels that suddenly saw flooding or fire spreads were.

The basic ideas of damage control aren’t exactly rocket science. You want to have redundant systems, you want bulkheads and compartments to ensure that anything bad isn’t spreading from one location to another, and you want to be able to maintain power. If you can manage those three things, chances are good your vessel will get you home. In practice, this has sometimes proved difficult.Such as when the KNM Helge Ingstad experienced flooding in rooms where key valves that needed to be shut were found. To avoid this, many of the key pipes and thru-hull fittings on the Amiral Ronarc’h have remotely operated valves that can be shut from the level above where they actually sit. This is done with pneumatic controls, ensuring that you are able to shut off the pipes even during a total loss of power.

A damage control detail that is obvious when moving around on the ship is that Naval Group does not cover things up if it isn’t necessary. You might have opinions about the look of bundles of unpainted and uncovered cables running along walls and under the roof, but the stated goal is clear. If a cable starts to act strange, it is visible, you can feel if it is warm, and if there’s an issue, you just pull it out and if needed insert a new one. Same goes for piping, although pulling out a faulty piece and replacing it is naturally not possible in the same way.

In addition, roughly halfway from the bow to the stern you will find a double watertight bulkhead with a narrow space in between. This is to at the very least stop flooding from going from one half of the ship to the other, and is of additional importance as many of the key systems are duplicated between the front and rear halves of the FDI. This includes traditional equipment, such as the six 500 kW gensets being spread out three in the front and three in the rear. The usage of several smaller gensets instead of a few larger ones ensures that the power supply is always at the appropriate level, with all gensets having an automatic start function and a new unit will be online producing power within 2 minutes of the system sensing the need for more power. Having several smaller sets also ensures that any issues encountered will affect only a relatively limited part of the power supply. In addition, there is a seventh genset in yet another location (in the hangar, to be precise), which is the backup to the backups, and has an independent air start to ensure that whatever happens, you will be able to get it turning. This is also the recommended unit to repower the ship from, in case you suffer a complete blackout.

The powerplants are also split. As mentioned in the last post, the setup is CODAD (combined diesel and diesel) meaning there are two diesels driving each shaft. That in itself create a level of redundancy, which is further enhanced by the engines being staggered to make sure that any single hit does not wipe out both shaftlines. The rudders are also split, with their own independent machinery and rooms. While the two rudders usually work in tandem – following acoustically optimised laws of rudder movement patterns – if one gets damaged or otherwise out of order, it is possible to drive them independently. Another pair of moving fins is found further to the front, where a pair of automatic stabilisers work on steadying the ship (there were video released from an early test drive, where the stabilisers were not activated, which raised questions about the stability of the ship. While the seas were relatively calm during my trip, the stabilisers were active, and I thought the ship was well-behaving in the Atlantic swell). These are non-foldable, as that gives a better acoustic signature, but they do not protrude beyond the vertical plane of the hull (i.e. you can put the ship alongside a quay without worrying about the fins getting crushed).

So what happens when someone tries to hurt the FDI? As discussed in these posts, the ship is rather well-equipped with countermeasures, including both hard-kill and soft-kill solutions.But sometimes even the best laid plans aren’t enough.

The Marine Nationale has decided to maintain a dedicated engineering control room. This is despite the fact that most of the functions usually handled there is now found in the integrated platform management system, which is accessible from locations all around the ship, including from the bridge. The reasoning has to do with safety and performance in emergencies. Having a dedicated propulsion and systems watch team gathered in one place creates a small centre of excellence, and also allows for more eyes on the systems part of things compared to putting the people in charge of it on the bridge. And when something bad happens, it gives a natural location from where to lead and coordinate the damage control parties. A key piece of the damage control situational picture is the DCTMAT damage control situational picture tool, which not only is one of the key tools for the one leading the damage control effort, but since the situational picture is shared throughout the ship, it also allows the commanding officer to keep an eye on the situation without constantly calling in to check for updates (and being a distraction for those actively involved in the damage control effort).

You are also able to handle all functions needed to keep the FDI moving from the position of the flying control (FLYCO), the working station up high in aftmost part of the superstructure which generally is responsible for what happens on the flight deck. This really comes into play only when you have a catastrophic event such as the whole bridge being blown away, as while you can handle all the things needed – steering, power, propulsion, IPMS, … – the simple fact that the window is directed straight to the rear over the flightdeck means your watchkeeping is bound to suffer a bit. But for getting a wounded ship back home, it is significantly better than direct control on the engines. For watchkeeping while the bridge still is there and functioning, a typical watch is three people – an officer of the watch, a 2nd officer of the watch (whose duties include navigation), and one at the helm. Both bridgewings also have control stations with physical controls to be able to control the vessel from these during docking or other maneuvers in tight waters.

And speaking of really bad things – yes, the vessel is CBRN-protected with a citadel function where you can enter through a multi-room airlock with showers and changing facilities. The airlock is relatively close to the medical station, where in a relatively large space there is a procedure room allowing for a limited set of procedures (depending on whether the navy in question has decided to embark the personnel needed, a common complement is one physician and one nurse), a physician’s office, as well as four beds for patients you want to keep an eye on or don’t want running around on the vessel making other crew sick.

But keeping the vessels running is equally important during peacetime.

The commander of the French Navy is set to have 15 frontline frigates, made up of two Horizon-cass AAW-destroyers (yes, France, you aren’t kidding anyone), the eight FREMMs, and the La Fayettes until they are replaced on a one-by-one basis by the five FDI. Those fifteen are expected to handle submarine hunting in the North Atlantic, escorting the carrier battle group, operations in the Mediterranean, any other issues arising (such as insurgents firing ballistic missiles on one of the key shipping bottlenecks of the world), as well as NATO missions such as the Standing NATO Maritime Groups. Needless to say, the force will be stretched thin, which also means that the vessels will have to spend a lot of time out at sea. And the French are doing that, with a mind-blowing 80% availability.

This is based on a number of different factors. To begin with, the Marine Nationale is employing double crews for a number of vessels, allowing the vessel to spend as much time as possible out at sea, without working the crews to exhaustion and managing the significant blow to retention that such an operational tempo tends to cause. In addition, in a way that will sound familiar to my Finnish readers, the armed forces work in close cooperation with domestic strategic partners. For the navy, Naval Group has a contract as the prime contractor responsible for in-service support throughout the lifetime of the ships. This has been a key part of ensuring that the FREMM have reached the 80% target, and experiences from this contract and maintaining the vessels in practice have heavily influenced the design of the FDI. When walking through the vessel, you will regularly find bolted panels in the floor, roof, or walls, which are designated routes for when you need to change some major piece of kit which you can’t just carry out. While most modern ships will feature designated “cut-and-then-weld-here”-locations in the hull and superstructure, the usage of bolted panels takes this a significant step further, and e.g. changing a genset can be done in just a week, without any drydocking or cutting and welding of the plates. The gensets are also based around Scania’s commercial truck engines, meaning spares and replacements are readily available. Taken together, all this means that admiral Nicolas Vaujour, Chief of the French Navy, was able to sit down at the Paris Naval Conference with the First Sea Lord present, and note that while he has fewer frigates and destroyers than his British counterpart, he is able to have more of them at sea thanks to the high availability (though truth be told, the British having to decommission their Type 23 frigates at an alarming rate means he soon might have both more ships at sea and on total strength).

But most days things aren’t on fire or flooding, so that will be our next topic.