Four years ago I wrote one of the posts which saw some of the most divisive feedback any of my blog posts have generated. In it, I noted that the considering the cost overruns and delays of the Swedish A26 Blekinge-class, it was clear that while the submarine itself looks great, it also looks like it wasn’t the right choice for Sweden. In it, you will also find the comment that:

As noted, the combination of A26 being ordered as just a two-vessel class coupled with the complete inability to get a grip of both the cost and the timeline eleven years after order also sends alarm bells going off, and further bad news feel like a very real possibility.

Call me Cassandra, but last week I wrote an article over at Naval News headlined “Sweden’s A26 Submarine Programme Faces New Delays“. In short, time from contract in 2015 to first delivery has gone from seven to 16 years (2022 to 2031, +128%)! At the same time, the budget has gone from 11.2 Bn SEK (8.4 Bn SEK in 2014 levels) to 25 Bn SEK (+123%), or from 1.0 Bn EUR to 2.3 Bn EUR (adjusted to 2025 levels). HMS Blekinge which was supposed to have entered service three years ago will now roll out in six years time.

Complex systems tend to see both delays and cost overruns, but once you get past twice the budget and twice the delivery time, it’s hard to claim this to be business as usual. Let’s put it in perspective: JS Sōgei, the latest Japanese Taigei-class submarine, launched earlier this fall was ordered in fiscal year 2022 for delivery in 2027 and has a price tag of an inflation adjusted 460 million EUR.

You might say that it is unfair to compare a hot production line to a series of two boats, which would be correct (and part of the reason why buying just two boats is stupid). So let us instead look at the cost of the Italian U212 NFS programme, which I talked about in the last post. The first two boats where ordered in 2021 for 1,65 Bn EUR adjusted for inflation which included development, a training centre, “related technical-logistic in-service support (10 years)”, and a bunch of other stuff. First delivery six years from contract.

Some have wanted to blame changes to the specifications of the A26 Blekinge-class for the cost overruns and delays, but to be fair we have seen preciously little about any changes to the specifications besides the integration of new lightweight torpedoes. What has happened is rather straightforward:

- The original budget was knowingly set too low by the politicians, as it relied on export orders, to get the project started and approved by finance. This explains (part of) the budget increase in 2021,

- Industry was happy to accept that, as it was the only way of getting the submarines ordered and thereby saving the yard,

- While the politicians identified submarine production as a strategic industry they wanted to keep, they were not prepared to invest in the industry outside of direct orders, meaning individual projects will carry costs that in all honesty should be placed in dedicated budgets for infrastructure of national strategic importance.

But perhaps most crucially, no one seems to have understood that Swedish submarine design and production capability needed a rebuild, rather than just another order to keep it rolling. During the decades between the Gotland-class launched in the mid-90’s and the Blekinge-class twenty years later, a lot of know-how had simply been lost.

This last one seems to have been the hardest pill to swallow, and the main reason why a Swedish 1,925 t submarine now costs 2.5 times that of a 3,000 t Japanese one. Sweden who used to be one of the leading builders of non-nuclear submarines dropped the ball by not doing it for twenty years, and that was hard to accept. In social media you will see the blame laid on the Germans for mishandling the yard during their period as the owner, and on the Danes and Norwegians for jumping ship on Project Viking, a new submarine design that was being run as a joint programme at the start of the millennium. These accusations are not unfounded, but at the same time it is difficult to put all the blame on others for not ordering Swedish submarines when successive Swedish governments didn’t do so either.

But while much of the reasons behind the cost overruns and delays for the A26 Blekinge can be found in decisions made ten or twenty years ago, that realisation isn’t exactly helpful today. Some people seem to think I am somehow hostile towards the idea of a Swedish-designed and built submarine – an accusation I never quite figured out what they base it on. On the contrary, few individual military systems are as helpful for Finland as a strong Swedish submarine arm backed by a solid domestic industry. As such, let us start with the reality of where we are today, and look towards the future. What should Sweden do from here on to ensure a healthy capability to design and build submarines?

To begin with, a quick look at the current Swedish submarine force: Sweden have one Södermanland-class submarine built in the late-80’s. This boat, HMS Södermanland, was, together with sister HMS Östergötland heavily upgraded in the early 2000’s to receive air independent propulsion (AIP) and a bunch of other new features. It is these two submarines the A26-programme is supposed to replace, with the original 2010 announcement being that they would leave service in 2018 and 2019. HMS Östergötland was mothballed in 2021, while HMS Södermanland received a life-extension programme to ensure another decade of service life. This runs out in 2028, the year the submarine turns 40.

(Both vessels were originally part of the four-strong Västergötland-class of diesel-electric submarines, but got a new designation following the MLU)

In addition to HMS Södermanland, there are three boats of the newer Gotland-class, who all have now undergone their MLUs, allowing for service deep into the 30’s without any major issues. However, these are built in the 90’s, and as such there is an obvious need to replace them as well at some point. With any submarine taking years to build, and the politicians having identified a need for a new class to replace the Gotland-class starting in 2038, things are starting to look just a bit tight. On the positive side, the current schedules do seem to still allow for preliminary design work to start in a few years, using resources at FMV and Saab which should be ready with their part of the A26 Blekinge-programme by then. This could then be followed up by the detailed design and production contract in 2028, allowing ten years for production and sea trials, and would allow the building of the new submarine on the production line evacuated by HMS Blekinge when it is launched in 2028.

In other words, we would see vessels being delivered in 2031, 2033, and 2038. That’s a significant step up from 1996, 2031, 2033, but that’s still a five year gap between deliveries. And it also seems obvious to ask what happens after the last Gotland-replacement submarine is delivered in the mid-2040’s, just some ten to fifteen years after delivery of HMS Blekinge? Since we already noted that the disaster that befell the A26 budget and schedule was due to uneven rhythm in design and production, and with virtually no potential export customers left for the A26, one can’t help but ask whether things could be even smoother?

(Hat tip to George over on Twitter who posted the USNI interview with Lt. Jeong Soo “Gary” Kim, USNR, linked above)

Since we already mentioned the Taigei-class as being cheap, let’s look a bit closer at the current Japanese submarine series. Because apparently they are doing something right, since you could have ordered two Taigei-class boats the year the Blekinge-class was originally to have been delivered, gotten them delivered four years before HMS Blekinge and HMS Skåne will show up, and the whole cost would have fit into the budget overrun, while still leaving you with 380 million euros of change from just the overrun part of the total submarine budget. If you would have taken the whole programme budget of 2.3 Bn EUR, you could get five Taigei for the price of two Blekinge. Why is that?

To begin with, Taigei is not cheap because it is bad or cutting corners. While comparison of submarine capabilities is always an opaque field, the general consensus is that it is one of the finest AIP submarines in service with an ability to stay hidden for weeks without snorkeling, and they are quite likely the best ocean-going non-nuclear submarine found anywhere in the world. Yes, it is not what Sweden with its focus on the littorals needs, but common sense is that that difference should make the Taigei more expensive when comparing it to Swedish boats.

It turns out that what makes Japanese boats cheaper is that Japan has a very simple yet unique system for handling their submarine fleet. Ever since the sixties, two yards have been building their submarines. Every year, the yards alternate in delivering a submarine. This is regardless of how large the submarine force has been at any given point, and the fleet size is instead regulated by retiring the oldest submarine on the force whenever a new one enters the fleet. If there is a need to grow the force, no submarine is retired that year, and if there is a need to shrink the force, you simply retire more submarines.

But this is madness, I hear you scream. You can’t just keep retiring perfectly good submarines!

(I know you did, because that was my reaction when listening to the USNI presentation above)

There is however method to this madness. To begin with, while submarines can serve forty years, it isn’t exactly ideal. That require a solid MLU at some point, the one for the Gotland-class HMS Halland in 2022 cost approximately 113 million EUR adjusted for inflation (a sum that likely included relatively little in the way of non-recurring costs, as the MLU had been developed for and first ordered for just the two other boats in the close), or a quarter of a new-built Taigei. It is also well-known that vessels become increasingly maintenance heavy during the latter stages of their lives, and as such the cost to keep a thirty year old submarine running is quite a bit higher per hour at sea than that of keeping a ten year old boat in trim. Let’s look at a few figures.

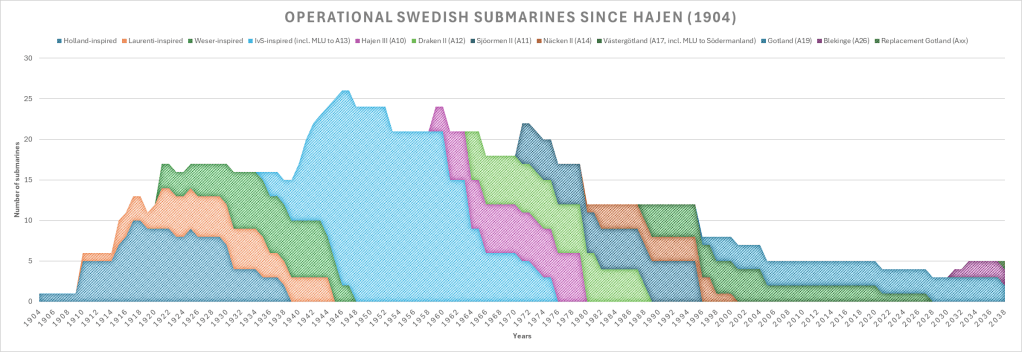

The illustration above is inspired by and based on one found in Fredrik Granholm’s excellent “Från Hajen till Södermanland – svenska ubåtar under 100 år”, and deals with operational submarines – as such it is lagging a bit compared to when the vessels are commissioned. For the early years this shows a rough division into different types of submarines based on their general design characteristics, while starting with the post-war Type XXI-inspired designs the individual classes are displayed. Click on it to see an expanded version with more details.

That Sweden had 26 operational submarines at one point during WWII is however of somewhat limited value for this discussion, so let’s zoom in on the period from 1980 when the 1950’s-vintage Hajen III (A10) class was retired and the submarine force settled at 12 boats for the next fifteen years.

Note that when extending the timeline into 2038 I have made the assumptions that 1) HMS Södermanland will indeed retire in 2028 and not get another extension, 2) HMS Blekinge and HMS Skåne won’t be delayed further, and 3) one of the Gotland-class will be replace on a one-to-one basis in 2038. You can argue with all three points, but currently this is the most likely future as indicated by open documents.

What I would like to draw your attention to is that for a considerable time in the not-too-distant past Sweden operated 12 submarines, and as late as this side of the year 2000 Sweden operated eight submarines. Japan currently has a fleet of 23 submarines in operational service, which is a lot more than Sweden has had during my lifespan, and an increase from a fleet of 15 submarines the JMSDF operated in the 1990’s. But remember that Japan keeps two yards in service, while Sweden would like to have a single one operational. If you cut the Japanese force in half, you end up more or less at the twelve-boat fleet Sweden had until the mid-90’s, while if you instead look at the lower end of the Japanese force you end up with just seven or eight boats, the size of a fleet which the Gotland-class started out as part of!

However, the number of submarines is only part of the question.

Perhaps even more relevant for the question of how large a submarine force Sweden can operate is looking at total crews rather than just the number of boats, as trained submariners are difficult to come by, takes years to train, and need to be paid. Higher degrees of automation has seen crew sizes become reduced per submarine. This also means that crew numbers have come down even faster than the number of boats, but also that rebuilding the fleet to eight boats would require something like 180 submariners, instead of the 206 that was the number back when Sweden had eight submarines on the force. In essence, you’d get crews for nine modern boats from the crews of eight boats back in 2000. It’s not a huge shift, but in a day when armed forces everywhere are struggling with recruitment and retention, it’s not nothing either.

I would like to reiterate once more that the Japanese example isn’t some kind of hypothetical study or rapid build-up due to a growing Chinese threat, but an operating principle which has proved to be a functioning – if unconventional – solution for submarine-building for sixty years.

Okay, so let’s say Sweden shifts to a Japanese model, what would that mean? The first thing to do would be to order another pair of A26 Blekinge class submarines for delivery in 2035 and 2037.

“Wait”, you say. “Another pair of a ridiculously overpriced and late design?”

Yes. The issue with Blekinge isn’t that the design in itself is intrinsically bad or expensive (at least that almost certainly isn’t the issue), but rather that it got to be the “Let’s learn how to build submarines again”-project while also paying for twenty years of not properly maintaining or upgrading the shipyard. With these issues out of the way, boats number three and four will almost certainly be significantly cheaper, even if you would want to borrow another trick from the Japanese and Italians and make some modifications to create a new sub-class through iterative improvements. Now your fleet would stand at seven subs by 2037 – three Gotland, and two + two Blekinge – and with a submarine delivered every second year you would see a fifth and sixth submarine delivered in 2039 and 2041 (either a new design or another iterative development) you could start retiring the Gotland-class by around 2040 after 30+ years of service and still maintain an eight boat-fleet.

(You might also at some time during this post want to point out that Japan is a much larger and richer country than Sweden, and you’d be correct. The country’s GDP is six and half times that of Sweden, but it also spends just 1.8% of GDP on defence, half of what Sweden aims for, so in essence we are talking about a defence budget that is somewhat more than three times as large. However, I will argue that that comparison is an argument more relevant for the discussion of whether or not Sweden should try to fund its own submarine production capability or not, and not about whether the Japanese way lead to cheaper life-cycle costs once you have made the decisions that you want your own submarine yard, which the Swedes have done I and which is a decision I don’t see them changing any time soon)

And added bonus is that if you start double-crewing the Gotland-class today – something that is sorely needed in any case to get the maximum number of sea days out of the class during the next five to ten years when the Swedish submarine force shrinks to its lowest since 1910 – you would also have trained crews ready to enter service with the Blekinge-class as they come into service.

The big issue obviously comes in 2047 when the ninth boat after HMS Blekinge comes into service, meaning you either start growing the force past eight boats, or retire HMS Blekinge after just sixteen years of service. Blasphemy!

However, if we calm down, a quick look in the books show that that’s also more or less the point at which HMS Blekinge would need to start planning for its 150 million EUR MLU, which is a direct saving that can be put towards paying for boat number nine. Also, it might be worth a quick look at the history books to check what happens when Swedish submarines are retired.

Of the four classes that has seen service at some point during our period of investigation from 1980 and up until today (and not counting the Gotland, of which all three still are in service), the fate of the boats looks as follows:

Good boys go to heaven, Swedish subs to Singapore.

Okay, that’s an oversimplification, but if we start with the Draken-class built between 1957 and 1962, they are the last class to have seen a significant number scrapped (with HMS Nordkaparen becoming a museum ship). The Sjöormen-class was sold in its entirety to Singapore, as part of which four where modernised to become the Challenger-class while the fifth was used for spares. Of the three Näcken-class submarines, one was leased to Denmark, one became a museum ship, and the third is the single Swedish submarine built since 1962 that has been scrapped by the Swedes themselves. Of the Västergötland-class, as mentioned two became the Södermanland-class of which one is in service and one mothballed, with the other two undergoing a similar deep MLU and being sold to Singapore as the Archer-class.

Maybe, in a world where Sweden would be able to series produce newbuilt submarines for their own force at the 500 million EUR mark instead of artisanal boats for 1.15 Bn EUR a piece, just maybe, there would be a market for exporting 15-20 year old submarines? It might be that that market is then Chile or Romania as opposed to the Netherlands (or perhaps we can create a Finnish-Danish squadron with two-three boats relying heavily on the Swedish maintenance and training infrastructure), and certainly not every submarine would find a buyer, but it isn’t difficult to imagine a scenario where enough boats would find a buyer that the overall cost for the submarine life-cycles would be more or less the same as for a more traditional eight-boat fleet using the submarines for 40 years. Considering that this would:

- Avoid the uneven workload in the yard that one new class every fifteen years leads to, in favour of a continuous flow of work in two-year cycles,

- Minimise technological and budgetary risks through incremental developments every few years rather significant leaps every decade,

- No need for MLUs,

- Major savings in maintenance costs per operating hour due to a younger fleet,

- Significant export opportunities of relatively young surplus submarines (which also would benefit domestic industry by providing MLU-opportunities as part of export packages),

- Higher value when scrapped due to better opportunities to cannibalise the submarine for spares and more modern materials and equipment leading to higher percentage of reusable components.

Why then, if this is so great, is Japan more or less unique in managing their fleet in this way?

The issue largely comes down to politics and psychology. Major acquisitions tend to make headlines, and if you every second year order a new boat for 500 million EUR the defence minister will every second year have to explain why the Navy is getting a new submarine while selling or scrapping a perfectly functional one, and that over the long run this is in fact cheaper. To work it also needs consistency, you can’t skip the buys just because the world seems more peaceful for a decade or two. Japan managed to do this during the 90’s, which means that they are in a good position to grow now that the Chinese threat is becoming more urgent. But not every country has the kind of political leadership that can refrain from making major defence cuts just because the Cold War ended. It also need a certain minimum fleet size to work. The Japanese have shown that with two yards it will work with 15-20 submarines, and it is likely to be roughly scalable to one yard and 7-10 boats. How much lower it would work is anyone’s guess. It isn’t a black or white proposition, but a balance of both how hot you need your production line to be to get measurable benefits as well as how short a service life for your submarines you can tolerate. If you accept a fifteen year service life and one boat every third year, you could do this with a five boat-fleet. One boat every third year and a seven-boat fleet would give your boats 21 years in service, which while a far cry from forty is still a perhaps more acceptable number than fifteen (and incidentally, what the three A14 Näcken-class submarines served before retiring around the year 2000).

Though as said, the days when Sweden had eight boats aren’t a distant memory from the Cold War, but how the fleet looked when the Gotland-class entered service. So if submarine building really is to be one of two “critical defence interest” as identified in official documents, you would be excused to think that also meant having a submarine force you can’t count on the fingers of one hand (and there are already discussions about ordering four Gotland-replacements to raise the fleet to six boats in the early 2040’s). And to be honest this whole discussion comes down to a classic ‘Choose any two of the following three’.

If you operate a small number of your own submarine design, they aren’t cheap.

If you operate a small number of cheap submarines, they aren’t of your own design.

If you operate cheap submarines of your own design, their number isn’t small.

I do feel for the people over at FMV, the Navy, and in the industry who now has to explain why stupid decision made fifteen years ago led to this dumpster fire of a project, while at the same time trying to make submarine production as a critical defence interest work. However, if there now honestly is a political will to ensure Swedish submarine production know-how will remain relevant, the worst part of the rebuild should by now be over and there are in fact opportunities going forward. But, succeeding will need courage from both politicians and the other stakeholders to think in new ways and ask hard questions about what the cost of maintaining the submarine industry really will be, and how to manage the fleet as efficiently as possible. Adopting a Japanese model and growing the fleet back to where it was when the Gotland-class entered service might be one solution. It might not be the only solution, but if you keep doing things how they always have been done, you will keep getting the outcomes you have been getting.