Continuing our series of book reviews pre-Christmas, this one is a real gem for any Finnish-speakers out there.

Lake Ladoga is big. It is big enough that it will comfortably make the top-15 lists worldwide regardless of how exactly you measure areas of lakes, but most importantly it is big enough that is has shaped everything happening in the Russo-Finnish border regions for centuries. And sometimes that leads to strange situations. Such as the Italian Navy arriving by train to try and starve Leningrad.

The general outlines of the operations in Europe’s largest freshwater lake in the summer of 1942 are if not exactly well-known then at least recognised. Germany was besieging Leningrad, the sole way in was by boat over the lake, and in an attempt to shut down that lifeline a combination of Italian and German vessels were sent to operate on the lake together with their Finnish hosts. But a detailed account has so far been missing, and that’s a real shame, because it is a truly fascinating story.

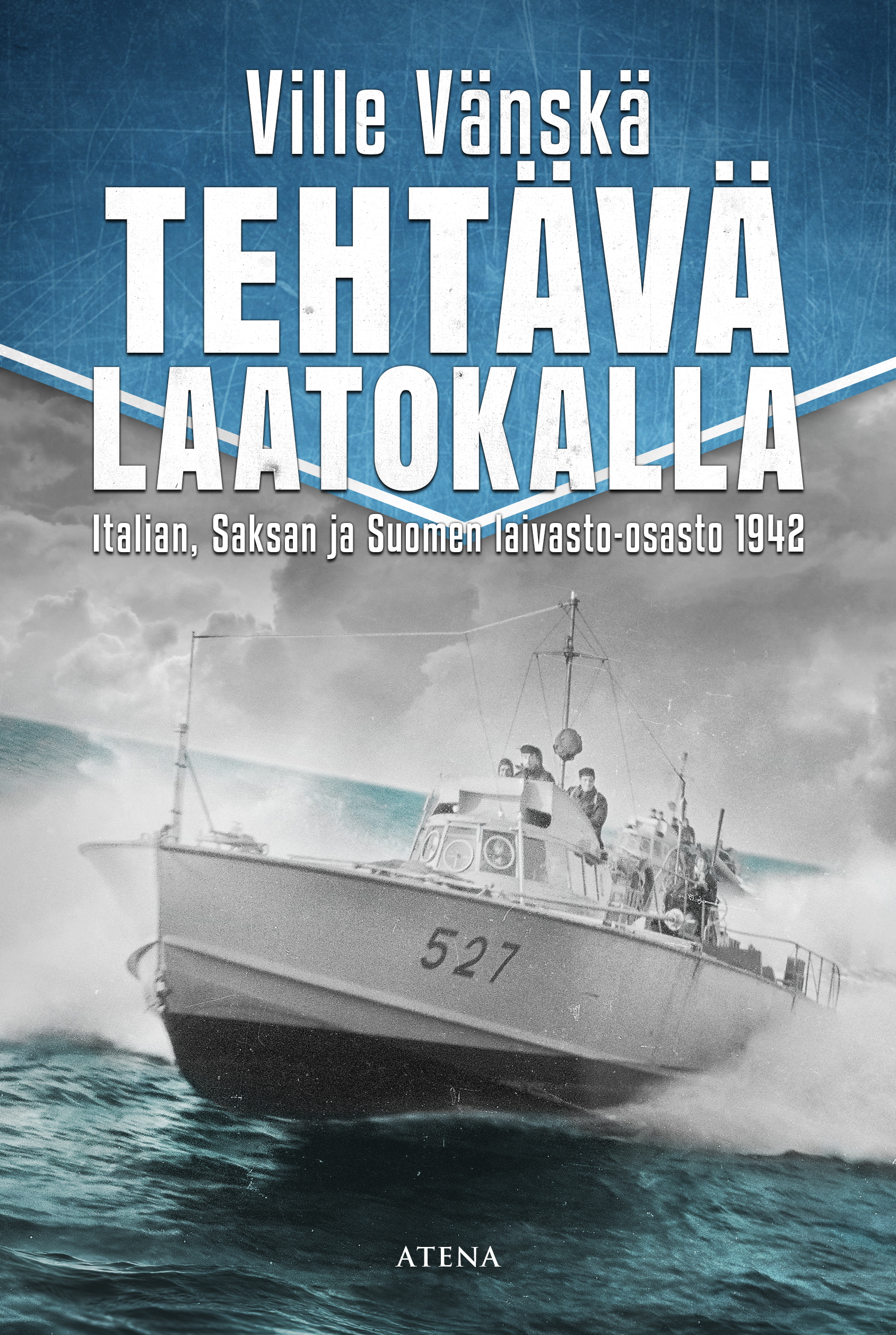

Finnish Naval officer Ville Vänskä finally has solved this with Tehtävä Laatokalla (ISBN 9789511453246), and this really is a case of truth being stranger than fiction. The whole initiative wasn’t officially sanctioned, and once the Germans started searching through European waters for suitable small craft that could operate in the confined waters of the lake things didn’t exactly get off to a smooth and clear start either. Eventually, however, a motley force from three countries and four different services was assembled under Finnish command. The gallery of persons involved is also something to behold, with Italian swashbuckling torpedo-boat crews and officers led by Capitano di corvetta Giuseppe Bianchi, Kriegsmarine officer Hans-Joachim von Ramm who was reluctant enough that he simply left the base and returned to Germany, pilot and aircraft manufacturer Friedrich Siebel who designed and commanded the Siebel ferries, and a number of Finnish officers led by Kalervo Kijanen, who must have been wondering how they all ended up in this. An interesting question which the book raises for me personally is how the formative years of the Finnish Navy was shaped by foreign influences, and in particular what role the Italians and Regia Marina had in this. It is well-known that Finnish Army-thought was based on a combination of Prussian and Czarist-Russian traditions, but for the Navy the ideas seems to have come from elsewhere.

If you are looking for accounts of naval combat in unlikely places, the book does provide that. However, reflecting the nature of the unit and the story behind it, the better part of it deals with the political game behind it, the logistical struggle of moving the vessels to their new (temporary) home in the forests of Karelia, and the frustrating struggles with actually getting anything useful done. This isn’t action from cover to cover, but that would not have been the story of Naval Detachment K, as the multinational joint force became known.

For me personally, this is in fact where the great value of the book lies. It would have been easy to gloss over the fact that getting a squadron of torpedo boats over the Alps into the lake was a significant endeavour in its own right, or that individual officers perhaps should think through the diplomatic ramification of any ideas they have before acting upon them, but Vänskä doesn’t do that. Instead, he discusses the realities of the work behind the scenes, and I do think that is what makes the book feel so valuable to the current reader. With Finland having joined NATO, a historical example of setting up a new force from scratch, choosing equipment for it, and dealing with both personal, cultural, diplomatic, and technical restrictions and frictions is something that is of value to any number of people working within the defence forces, other authorities, defence or logistics companies, or just reservists who want a better of understanding of how hard these things are when done for real.

While some of the pictures are classics from the Finnish wartime archives, there are also a number of ones you likely haven’t encountered – including from personal collections. A key breakthrough for the book was in fact when Vänskä stumbled upon Kijanen’s personal copy of the Italian “Attività della marina in Mar Nero e sul Lago Ladoga”, complete with the detachment commander’s personal notes in the margins!

I highly recommend the book. The illustrations are good, and include a significant number of photographs, but also well-done drawings and maps. The use of large info-boxes for particular topics (such as the story of individual officers) is good, but they could perhaps have been marked somewhat more clearly as being outside of the main text. I sincerely hope – even if I know it is unlikely – that we could see English or Swedish translations of the book, because not only is it a marvellous story, it is also one that include valuable lessons for the modern day.

Book received free of charge for review purposes.

Have intended to pick this one up a couple of times but the shelfs in the stores has been empty already.

So the interest for the subject, littoral small craft operations, is definetly there.

We also had some officer(s) sent to study S-boot operations in the English Channel.

Dont know if we have good studies on what they learned.

The subject is also very topical and current as we have the Gulf of Finland area of operations forming and other littoral theaters in the Black Sea and Pacific.

And Russia has also given the first indications that it wants to exploit the fact that it has full control over the Ladoga now and form some type of LRPF bastion in Ladoga with its fleet of littoral and riverine vessels.

Good that we already decided to get the JSM.

I am a big fan of Jehu-class type of craft and would like to see more of them and with heavier armament.

And I would like to see an excercise where they are airlifted.

Hot damn, that’d be an interesting book to read. Thank you for the review!

Well I think you have to be able to read Finish as well as speak it! (grin)

While I have read a lot of WWII history, I never came across anything in regards to the book and your report so even if I can’t read it well done!

Found a copy, it was the last one in the store!

Have just started and already thinking if we should have some units in lake Saimaa after all?

(To foreigners, this idea is a long running inside joke within Finnish reservist circles).

But the interest that Russia has shown towards the Saimaa region, national road 6, the Parikkala-Vaasa axis and preparing their jump-off point around Lahdenpohja has to be taken just as seriously as the Airisto preparations.

Naturally it would have to be a volunteer force, Detachment Sääksi type of unit.

Missions could be SAR, troop transport, logistical support, possibly minesweeping.

Question inspired by the book related to logistical challenges in present day.

Ukraine is starting to rebuild its navy together with the UK/Norway/Ukraine Maritime Capability Coalition (IMO we should join) and has already received two Sandown-class minehunters as donations.

But as Turkey invokes the Montreux Convention the ships cant travel trough the Bosporus.

My idea with the proposal to donate the Rauma-class has been to transport them trough the Rhine–Danube route.

Both the Rauma and the Sandown have the dimensions to transit the route.

Is there some treaty preventing this? Even if disarmed for transit?

Danube should be free for navigation, nothing Orban or Serbia can do about it?

Well this got answered, Russia is close to succeeding in starting a conflict in the Balkans after years of subversion towards that goal.

Control of the Danube gives influence over Eastern and Central Europe.

If Russia cant take the Danube mouth from Ukraine then a Serbian satellite state is the second best thing.