In previous bills in the area of defense policy, the government has identified the combat aviation sector, the underwater sector and integration-critical parts of the C4-sector, such as sensors, telecommunications and secure communications, as essential security interests for Sweden.

Swedish Defence Bill “Totalförsvaret 2021–2025” (Proposition 2020/21:30)

Those who have followed the blog a longer time knows that for almost a decade, coverage of the Finnish HX-program was a staple. Following the decision to go for F-35, the number of posts on Finnish fighters have trailed off, due to the fact that there are simply not too many interesting details coming out of the program. On the whole, things appear to run smoothly, and to anyone wanting more details I can recommend the Air Forces’ latest long read.

So while waiting for more details on JETX, or some interesting drone or transport program, let’s turn our eyes to Sweden, where our friends and allies are currently in the early stages of Vägval stridsflyg (“Fork in the Road Combat Aircraft”), or what they will do after JAS 39E Gripen.

Currently, the lifespan of 39E is envisioned to stretch out to 2050. Air combat is unlikely to go away, and as such some kind of airborne platform is expected to first complement and then replace it after that. What the Swedes are now facing is the choice of how to go about procuring that platform, which in essence boil down to three options: design a new indigenous fighter aircraft, collaborate with international partners to build a fighter, or buy something in existence (possibly backed up with some kind of technology transfer and more limited participation in the program, such as is the case with F-35 for Finland). As among the options on the table are developmental ones, the decision needs to be taken with enough time for a new fighter to be developed if that is the outcome of the process, meaning the decision need to be in place roughly by 2030 – which is also the timeline stated by the Swedes.

Let’s be real, it is extremely difficult to imagine Sweden building their own sixth generation fighter. The first issue is just straight up cost. The UK-Italian-Japan GCAP has an expected program cost of 45 billions according to Leonardo, a figure which is (indirectly, as the text was written well before that interview) disputed by Justin Bronk of RUSI, who believes it very difficult to get below the 100 Bn GBP mark of the Eurofighter program. The NGAD program is more of an enigma, but my understanding is that well over 11 Bn USD has already been directly invested in developmental efforts, added to which comes the undisclosed amount the DARPA flight demonstrator cost, and an additional 20 Bn USD is expected to be needed to get the R&D phase finished, and then the aircraft would be procured at “at a cost of multiples of an F-35”, pushing it into the same 50-100 Bn USD space as occupied by the GCAP.

Now, a careful read of the numbers above reveal I have not adjusted for inflation, nor have I bothered converting exchange rates, because to be honest the uncertanities of programs stretching over 20 years into the future with partly classified budgets and differing ways of calculating total program costs means there’s really no use in trying to come up with a detailed estimate for the cost of a new Swedish fighter. And any estimates or number-crunching done will likely be met with valid criticism that I am under- or overestimating something. And I would like to leave it more or less here, but Swedish public broadcaster SVT stated that “estimates” place the cost of a new program “somwehere between 9 and 13 Bn EUR, potentially more”, and that needs to be ridiculed ehum, disputed, in more detail. I have honestly no idea whatsoever for how they came up with that figure, which is a quite close match to the HX budget for 64 basically unmodified aircraft with their first sets of spares and weapons. With inflation and their larger air force, Sweden is hard-pressed to even be able to replace the current force of Gripens with F-35s for 13 Bn EUR, let alone develop something new. It might be that they are using an extremely narrow definition where they are just referring to the cost of the R&D phase of the aircraft itself, and do not include any pre-studies or actual procurement (which granted, you will have to pay for in any case), nor e.g. integral parts of the overall system but which aren’t the aircraft itself (network ground infra, unmanned platforms, …), but in either case it is not a figure which will allow you to start from a blank sheet and end up with a functioning six squadron-strong air force twenty years later. And as such, I do feel one should point out what such a figure could be, and I stress the word ‘could’.

A quick back of the envelope estimate could be that developing it for 50 Bn and then investing another 20 Bn EUR/USD/GBP in procurement sounds like an optimistic, but not unreasonable estimate. Justin will probably say I am too optimistic. Justin is probably right, but let’s give Sweden the benefit of doubt. For a country with a GDP of just under 600 Bn EUR, a 70 Bn program would be something along the lines of 11.5-12 % of GDP, which spread out over say 25 years gives an average cost of 0.46-0.48 % of GDP.

To put it in perspective, this is 15-20 % more on average for the whole quarter of a century than the 0.4 % of GDP that is often quoted as the peak of both the Apollo program and the Manhattan project for the US.

Again, there’s huge uncertainties in all of the numbers above. If you want to make a really aggressive case by slashing my R&D budget with half, taking a third of the procurement cost, and then factor in that the Swedish GDP would continue to grow at the rates (~2.0 – 6.0 % annually) we’ve seen the last 25 years, things are looking rosier – with a total program cost of 38 Bn EUR and a GDP say roughly 20 % larger (700 Bn EUR) the project would only be 5.4 % of GDP, which spread out evenly over 25 years would give 0.22 % of GDP on average for a quarter of a century.

In either case, even these oversimplified calculations for all of their faults shows why while once upon a time in the West there were a bunch of countries with domestic fighter programs, and now even countries such as France and the UK (both in the 3 trillion USD GDP club, i.e. with well over five times the GDP of Sweden) simply aren’t willing to make an attempt at going for it alone anymore. Modern fighter programs are just huge undertakings.

And then we come to the more touchy subject, does Swedish industry have the capability to build a modern platform for the 2050’s and beyond?

The idea of developing a domestic fighter is based on the fact that the Swedes are very happy with the Gripen, and have a long tradition dating back to the closing stages of WWII of developing innovative fighters (as well as strike and recconnaisance aircraft). As noted this is also identified as a strategic interest at the parliamentary level, and seen as crucial both for the security of supply as well as for direct economic and spin-off effects at a national level. All of these ideas are correct, and the Gripen is in many ways a really neat piece of kit which in today’s skies is a serious contender against more or less anyone and anything. But does it provide the building blocks from which to develop the next generation?

Because, let’s ask the hard question: doesn’t it bother anyone seeing the 39E as the stepping stone to a 2050’s fighter that the exports so far has been to countries where the most serious adversaries (and with some margin) are some twenty-odd Sukhoi Su-30MK2? Everyone loves a good FLANKER, but these are about to turn twenty years old and even upon delivery were a step behind the more famous Su-30MKI. And sure there’s always politics involved, but in HX the situation seemed like it was the perfect scenario for Gripen (fixed budget, judged on combat efficiency of the total package, dispersed operations with large numbers of reservists involved, demand to be able to operate without outside support, …) and despite being backed up by two GlobalEyes the Gripen lost out to the F-35A in all categories. Any kind of concern what this might say about the state of the Gripen compared to the current international benchmarks? As said, the 39E is a very nice aircraft, and it will have a long and useful servicelife as one of the cornerstones of the NATO’s air power in Northern Europe, including by providing certain really interesting capabilities, but as a multirole-fighter, is it really one of the apex predators?

Granted, when discussing a new Swedish fighter in a NATO-context there is no rule that says Gripen’s replacement has to be the king of the hill. A lot of countries were happy flying the Northrop F-5 in different versions during the Cold War, relying on the support of larger and better aircraft from other countries to do the heavy lifting. This could also fit the budget better, with e.g. the baseline version of the KF-21 being developed in South Korea for reportedly a bit under 10 Bn EUR, providing a modern but somewhat limited fighter (which in the case of the Koreans are to serve are the stepping stone for the more developed versions). But I somehow have a hard time seeing Sweden knowingly developing something cheap and simple to replace the 39E and then settling in as a second-tier fighter force together with the likes of Slovakia and Bulgaria.

But enough of this doom and gloom. One option is obviously to just scrap the Swedish aviation industry and buy something of the market in 2050. A choice I would argue is as stupid as it sounds, because while Sweden might lack the resources and some of the capabilities needed to build a cutting-edge design on their own, the Swedish aviation industry is still extremely solid, the national economy is looking healthier than many, and the reputation as a reliable partner also means they likely would be welcome. Granted, most countries look at cooperation as the opportunity to get someone else to co-finance their new fighter in exchange for the junior partner getting to design the wheel wells and a final assembly line for their aircraft, but, while they bring their own kind of friction, international programs have seen seriously succesful designs (Panavia Tornado, the Eurofighter, SEPECAT Jaguar, late-mark Harriers, F-35, …).

A common design also is not tailored to domestic specifications in the way a fully domestic one is, but this minus shouldn’t be overemphasized. All fighters are compromises, but at the end of the day few countries have such unique domestic conditions there isn’t international programs that would be a fit, and neither does Sweden.

So, what are the Swedish options?

The US is going through some things right now, and incidentally that’s also the state of the fighter programs. Both the Navy’s F/A-XX and the Air Force’s NGAD are currently facing uncertain futures. But neither does the US seem to be looking for international partners, nor is it clear that Sweden would be interested in joining a US program at this point in time. Granted, much can change before 2030, but for now the US is an unlikely route.

Turkey and South Korea are both currently flying their own prototypes in the form of the TF Kaan and the aforementioned KF-21 Boramae. Neither of these are the aircraft Sweden is looking for, and Turkey likely fall away due to political reasons. However, South Korea as a potential partner – possibly together with Poland which has expressed intrest in the KF-21 – certainly is an option that may be in the cards. The Swedish and South Korean aviation sector (and defence industry in general) does provide some interesting cases of complementary capabilities, which means that the fit might be better than with some of the major players.

Leaving aside India, China, and Russia, that leaves the Franco-German-Spanish FCAS/SCAF (also sporting Belgium as an observer), which is unfortunately not moving along in the way one would hope. The workshare agreements between Airbus and Dassault are unsurprisingly a source of major debate, as is the question of the unmanned components of the program – note that Dassault already has an UCAV-contract as part of the Rafale F5-upgrade program, something that Airbus is not overly happy about – and in general the question of national priorities has been a though nut to crack. While the program might certainly be open for new participants – Turkey is apparently being discussed as a serious alternative – at the same time Germany eventually throwing up their hands and joining GCAP instead would not come as a complete surprise either. An issue here for Sweden is the timeline, which doesn’t line up, and any workshare agreements would obviously become even more complex and fraught with political infighting if Sweden was to join. But it would offer the opportunity to join a program which likely will have a serious European user group.

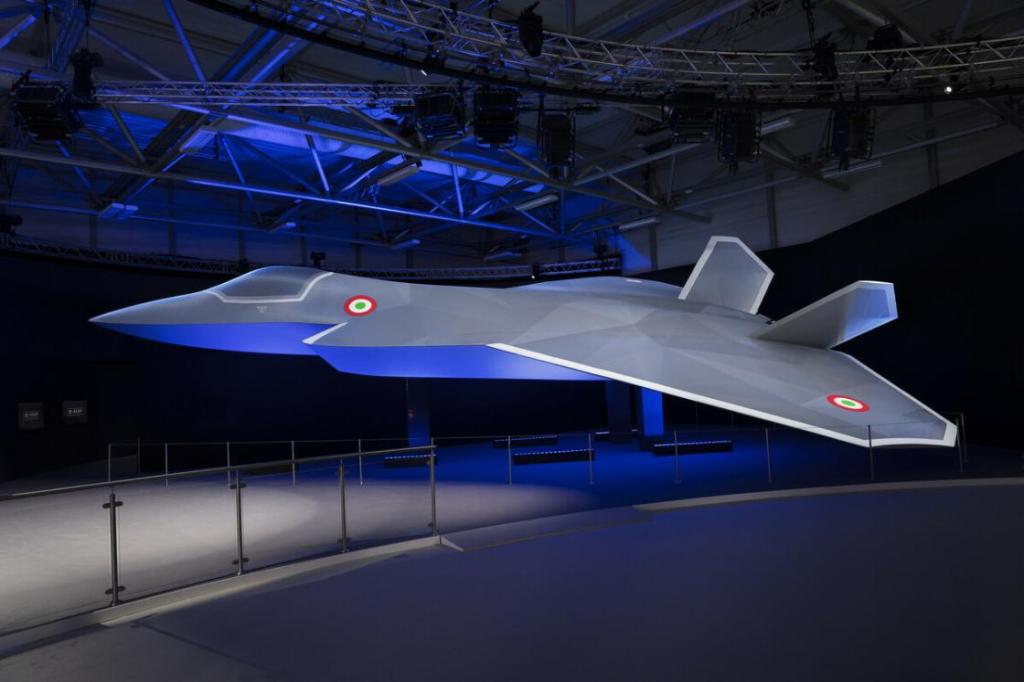

The earlier mentioned GCAP is, however, in my opinion the more promising alternative for Sweden. Not only is it somewhat surprsingly looking to be by far the healthiest of the Western next-generation programs – including the US ones – but at least outwards the cooperation seems to be going well between the UK, Japan, and Italy. The big question is whether the countries involved are happy to actually pay for what the development of the needed capabilities will cost, but recent signs are positive. A big questionmark surrounding the program is also the rumours about Saudi Arabia potentially becoming a partner. While the country would bring significant money, and it is a long-time buyer of British defence equipment, it is not a country most of the partners would want to be associated with, and there certainly are questions with regards to its ties with China. On the positive side, this also means that if Sweden could make up its mind and show up with a cheque for 20 Bn EUR and a proposal for their workshare, the partners might be even more interested than usual, thanks to it lessening the need to face the difficult Saudi-question.

One thing people have questioned is whether the GCAP is a suitable aircraft for a Swedish Air Force which traditionally has been more interested in relatively small single-engined fighters (the last twin-engined fighter in Swedish service was in fact the de Havilland Mosquito NF.Mk 19 which served a few years as a surplus buy). The GCAP aircraft – which the British designated the Tempest – on the other hand is a beast, with a clear emphasis on payload and range. This is unsurprising for the UK with their need to reach far out towards the Arctic or with long transits over European allies to reach the frontline, requirements which also led to the British development of the ADV-variant of the Tornado back in the days. The need for range and payload when living in Japan is also self-explanatory, and the country is a prolific user of the F-15 and the ‘super-sized F-16’ in the form of the F-2.

However, before writing off the fit for Sweden, it should be noted that a lot of things changed with Sweden’s NATO-membership. The frontline is suddenly quite a bit further away, and the need for longer endurance is certainly there. In addition, being part of the alliance means that there is bound to be changes to doctrine and tactics, to be added to the changes to doctrine and tactics that can be expected simply by the march of time and development of new technologies. As such, a larger platform with payload to work as the quarterback for a number of unmanned assets and able to carry the kind of larger and longer-ranged air-to-air and air-to-ground weapons that seem to be all the rage might be exactly what Sweden needs comes 2050.

But again, that would mean acting now, while the Swedish timeline sees the choice of what’s up next as being taken only in five years. As a matter of fact, Sweden was onboard what became the GCAP during the earlier parts of the program, but then dropped out, likely in part due to the schedule. If Sweden really wants a major piece of the pie, they will probably have to modify their own schedule to at least some extent. And with the stated 2035 entry of service of the GCAP possibly a bit optimistic, even a five-year delay would see it enter service “just” ten year before the 2050-mark.

Another interesting option stems from the fact that Saab already has been contracted to do concept studies for a potential platform. Or platforms. Or a system of systems. Everything is currently on the table, and with Saab’s involvment in the nEUROn UCAV-demonstrator program a decade ago, it isn’t impossible to imagine a scenario where Sweden buys the manned fighter of the shelf, and instead creates domestic unmanned companions for it, as the cost of these can be better adjusted to a set budget thanks to the wide variety of capability levels with everything from true multiroled UCAV operating independently, and down the complexity ladder all the way to smart decoys. But if the Swedish aviation industry really must get to develop the core component of the Gripen replacement – and that is likely to be a manned fighter – then you better start calling the Koreans. And if they aren’t interested, you might have to be quick to get onboard the GCAP to ride the Tempest.