As mentioned in my last post, the idea behind the FDI was that it will need to be able to do everything the FREMM does, and that obviously means that there needs to be the same or corresponding weapons, sensors, and combat systems onboard. Starting from the bow, we have an old familiar face, the classic OTO-Melara 76 mm deck gun (these days known as the Leonardo OTO 76/62 SR) in a stealth cupola. With cyber security being a key part of the FDI, it is interesting to note that the gun is in fact tested and declared secure. The basic OTO might be a Cold War-veteran, but in its newer versions it has proven to be an able and reliable weapon, which has shown its usefulness in the Red Sea where having a reliable air defence with some range and a serious depth of magazine against drones has proved valuable. The choice of calibre for deck guns is – as with everything – a compromise. Going up to 100 mm as the French did pre-FREMM or the 5’’/127 mm of e.g. the British Type 26-class frigates is an option that would bring more destruction per shell and in particular as the last anti-ship weapon or when providing gunfire support against land targets the heavier weapons carry significantly more punch, but they also add weight to the ship and will usually lower the rate of fire. Still, at a time when many vessels drop down to a 57 mm weapon – such as the Bofors planned for Type 31, Pohjanmaa, and the troubled US Navy FREMM-version of the Constellation-class – the choice of a 76 mm deck gun for a 4,600 ton frigate feels like a balanced choice. An interesting touch is that the gun can be controlled by the quick-point designator found on either bridge wing of the Amiral Ronarc’h. This is a handheld sighting device with a laser-rangefinder and so forth, which mostly is used by a person standing watch on the bridge wing to designate points and targets quickly and easily, and then at the push of a button send these to the combat management system. However, in certain cases it can be used to directly control the 76 mm deck gun. You aim at the target with your handheld sight, get the bearing and range, and push the button to send a 6 kg high-explosive shell going 900 meters per second at your designated spot.

It should be stressed that this is not how you normally would operate the gun – instead that would be handled through the normal combat management procedures by one of the operators at a multi-function station, but it is a functionality that is available if you have a very loose ROE and are expecting that targets can appear fast at close range, such as when transiting through narrow straits with a high risk of insurgency attacks. Under the standard method the gun would instead be directed by one of the fire-control sensors, such as the Thales STIR 2 which sport both X-band radar as well as visual-light and IR-sensors. The FDI also feature two mast-mounted Safran PASEO XLR, which feature “a high-performance gyrostabilized platform providing an accurate line of sight, a wide set of imagers with continuous zoom and high-power telescopes and an eye-safe laser range finder”, allowing for manual or automatic surveillance, automatic target tracking, visual identification, laser rangefinding, as well as the ability to either create and share target data, or then receive data from other sensors to know where to look. With two systems, a full 360o coverage is possible.

But while a 76 mm deckgun has proved to be extremely useful in today’s threat environment – in particular against flying and surface drones – the big punch of the vessel is found in the missile batteries. The French vessels are equipped with 16 Sylver vertical launch cells, and have space for an additional 16. The Greek Kimon-class does come fitted with all 32 cells right from the get-go, and include the MdCN-cruise missile – the French ones won’t get the MdCN, at least not yet, but as they are fitted for the same capability as the FREMM (and as their Greek counterparts) they are fitted with all the necessary subsystems (minus the full-length Sylver-cells), down to the physical switches in question. In either case, it is a serious land-attack weapon, sporting a low-observable design, high-subsonic speed, and an estimated range beyond 1,000 km.

The main weapon for the VLS-cells in either case is the Aster-family of surface-to-air missiles, with the Aster 30 being capable of bringing down aircraft out to an official range of 120+ km, though as always the ranges of air defences are highly dependent on what the target does, and under good circumstances the range reportedly is significantly longer than the quoted 120 km. The missile is also able to intercept ballistic missiles, and in both cases it is aided by the extremely potent radar setup of the FDI. The main radar is the Thales Sea Fire, sporting four fixed panels providing not only continuous 360o coverage, but also up to a full 90o vertical, a feature that isn’t a given on all AAW-frigates but is extremely valuable in the anti-ballistic missile role. The Sea Fire is operating in the S-band, is a GaN-base AESA-radar, and Thales likes to describe it as 4D, as it also continuously keeps measuring doppler effects on its targets. That might be marketing-speak, but there’s no denying that the radar is highly regarded. The air defence mission is also a key part of the task when the FDI serves as one of the multi-role frigates in the French carrier battle group. Being able to stay with the carrier is in turn part of the need for the 27 knot contracted top speed (the Amiral Ronarc’h has in fact repeatedly beaten the 27 knot mark during its first half year of sea trials, reliably logging 28+ knots).

But you can’t keep firing full-sized Asters at anything that comes your way without A) rapidly running out of weapons, and B) rapidly running out of budget to buy new ones. As such, the vessel is also able to mount a close-range defence system. The Greek vessels will sport the RAM Block 2, which holds 21 short-range RIM-116 RAM missiles. The French vessels are so far going down the fitted-for-but-not-with route, but Naval Group understandably is keen to point out that this would be an excellent spot for their MPLS. The MPLS (multipurpose and modular launching system) holds four trays that each can be loaded with a different box of missiles, and which also can be swapped out or reloaded at sea. A single tray can hold e.g. four MBDA Mistral short-range air-defence missiles, or 20 rockets (such as the Thales laser-guided 70 mm one, which has an anti-drone capability). This allows for a number of possible mixes, going from 16 Mistral all the way to 88 rockets, or an 8-44 split which allows for a decent last line of defence (together with the 76 mm gun) as well as the ability to counter a massed attack of surface and air drones. The system can also be used in an anti-ship role for small craft, sporting the Akeron MP missile, though in the case of the FDI it is difficult to find a situation for that particular weapon. Just use the main gun, rockets, or the two Narwhal 20B remote weapon stations fitted with 20 mm autocannons, which we haven’t mentioned yet.

The Narwhal might be a somewhat new feature, but as with the stealthily-cased 76 mm gun, this holds a true veteran. The 20B is sporting the French Navy’s long-time go-to-autocannon, the 20 mm modèle F2 gun, a development of the Nexter (formerly GIAT) M639, a development of the Hispano-Suiza HS.820, which was developed as a replacement for the legendary HS.404. The two weapon stations are placed in opposite corners of the superstructure (one towards the bow and to the port, and the other towards the rear and starboard) to provide a full 360o coverage.

But the really interesting stuff isn’t so much in the weapons – as said, with the exception of the as yet unfitted MPLS nothing here is particularly new and exciting – but in the not one but two centres where these things are handled.

The more traditional of these is the CIC – or Combat Intelligence Centre – where in a surprisingly large room at the base of the integrated mast there is room for fourteen operator stations, a fully digital tactical planning table, and the raised commander’s seat. As usual with these kinds of systems, all fourteen multifunction stations are able to do everything, though in practice certain functions that support each other are usually bunched together. However, in case of someone wanting to spice things up, the operators can shift places freely, and still have full control of their part of the combat process. Coordination is assisted by a number of large screens visible to all, which can be used to display key data or the situational picture. The vessel is equipped with all the usual datalinks, including Link 11, Link 16, Link 22, and JREAP. In the room next door there is the aviation control central, with the vessel usually having embarked a 11-ton class helicopter – NH90 NFH Caïman in French service, MH-60R Seahawk in Greek service – as well as a 700 kg unmanned system such as the Airbus VSR700.

So far there’s nothing out of the ordinary, but there are few interesting features. One is that there is a fifteenth operator’s station on the main bridge, which is completely identical to all the other stations in the main CIC with access to all the data and functionality of these. This one is situated close to where the commander’s seat on the bridge is, and as such provide the opportunity to in an instant get access to any information about the situational picture that might be needed, and even to take appropriate actions if the situation suddenly demands that.

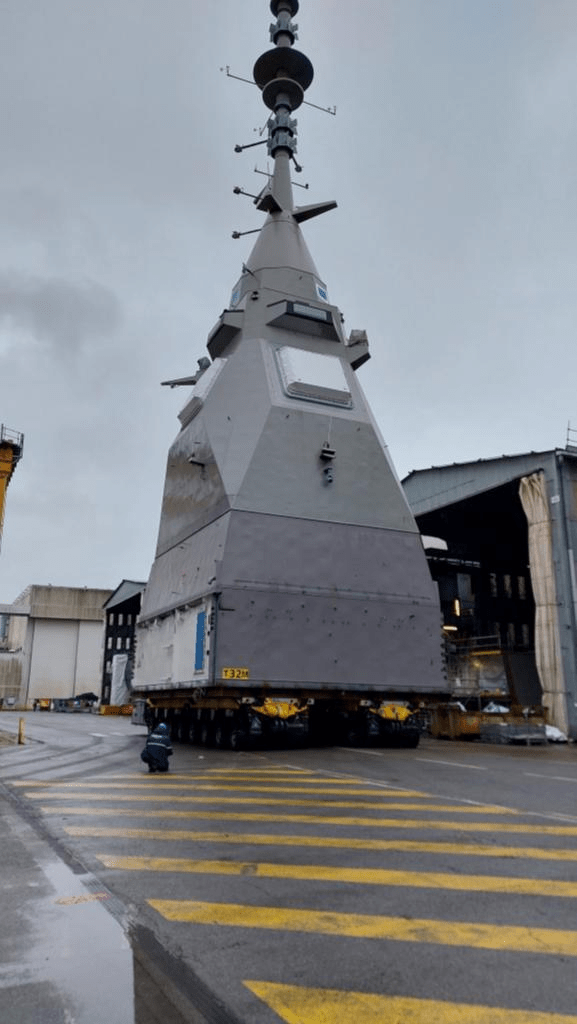

Another thing somewhat out of the ordinary is the fact that having the CIC situated under the main (and only) mast on the vessels, means that it is possible to build the mast and CIC as one complete unit fully fitted out already on the factory floor. This so-called PSIM (Panoramic Sensors and Intelligence Module) includes the mast, the base down to one level below the bridge, all sensors, one of the two identical data centers found on the vessel, cooling installations, and all the other things needed for everything mounted in and on it to function as it eventually will do on the ship. In other words, Naval Group can build the mast, install everything on it, and then run the combat management system and sensor tests on it using the very systems and operator stations that will work together when it is mounted on the ship. And all this while the hull is being built.

I will readily admit that I have not personally been responsible for the systems installations on any vessel larger than approximately 20 meters, but that is enough of an experience to know that if you make a hull, put a wheelhouse or other cabin on it, and only then start to do the interiors, systems installation, and wiring, you have quite a lot left on your to-do list after your boat began looking ready on the outside. Naval Group’s modular approach is seriously impressive, and reportedly speeds up things quite significantly, as the giant mast weighing in at 150 tonnes and being 42 meters tall (again, it isn’t just a mast, but also two levels including the CIC) can then be lifted onto the hull, plugged in, and everything is set to go. Together with the tried and tested SETIS combat management system (the outcome of half a century of developing combat management systems), and in general lifting a large number of the sub-systems related to weapons and sensors from the FREMM-class, this gives the vessel a high degree of maturity when it comes to much of its combat systems, even as the sea trials are still underway.

The PSIM hold not just the Thales Sea Fire and Safran PASEO XLR as mentioned earlier, but also navigational radars, UHF-communication antennas, panoramic cameras, ESM for radars, communications, and some other electronic signals, as well as a fixed panel IFF – again sporting full 360o coverage and continuous interrogation on all relevant bands.

If you start to feel like the phrase “full 360o coverage” is repeated often, that is because it is. The single pyramid main mast configuration giving the FDI (and the smaller Gowind-class before it) its characteristic superstructure is chosen largely because it ensures that anything mounted on the mast won’t be shielded by anything else sticking up on the vessel. This is a key part in ensuring the vessel is able to continuously track, engage, and communicate, regardless of where the target or friendly platform is and where it is moving.

But there are two things that really mark the FDI as modern. One is the emphasis on cyber security, with the yard proudly declaring that the vessel is the first warship to be cyber secure by design. You can probably argue about that distinction, but it is clear that we are seeing solutions which weren’t necessarily thought of as a necessity or even an option when the current generation of frigates and destroyers were designed. These include things such as two physically distinct data centers, both able to handle the full load of all necessary systems, and with the ability to swap from one to the other on the go in case of the loss of one, either due to technical failure or due to battle damage. Another focus has been on the cyber management system (again an in-house product from Naval Group), which is made to be operated by non-specialists, and as such feature easy to use step-by-step guides for any needed remedies. And when that doesn’t solve your issues, the vessel has the ability to transmit and receive code over SATCOM. Add to this network segregation and the other “usual” stuff, and you get a vessel that treats cyber security in the same way physical damage control has earlier been treated. The needs are obvious, and are driven by customer requirements. Marine Nationale recently hosted the latest iteration of their DEFNET series of cyber exercises, which this time around simulated a cyber attack on one of the La Fayette-class frigates.

The fully digital architecture is also one of the solutions to the “how do you fit a 6,000 FREMM into a 4,600 ton hull?”-question, as it allows for a number of physical cabinets to be removed, with the data centers replacing these.

The other thing that sets the FDI apart is found in a dark room easily accessible just behind the bridge. This is the asymmetric warfare bridge, which to be honest to me feels like a slight mistake in marketing. What it is is a combat intelligence centre for within visual range engagements, and as far as I am aware of it is totally unique on major surface combatants. A number of operators sit side-by-side in front of a giant wide-screen stretching the whole width of the room. This shows a panoramic view of the surroundings of the ships through the panoramic cameras (yes, once more it is full 360o coverage), as well as providing automatic target detection and tracking through an AI-module (not quite sure what the AI is doing there, but it’s 2025 so anything done by a computer needs to be using AI somehow), as well as giving several visual clues to the operators, showing the engagement arches of sensors and weapons. This allows for the operators to monitor, identify, track, and if need be, engage any threats appearing near the vessel, with for example the 20 mm guns, the MPLS (if fitted), or with the less-lethal noise/light effectors installed on the vessel.

To the whole “large-warships-are-dead-because-Ukraine-can-sink-them-with-surface-drones”-crowd: this is how you counter small surface drones. Good enough sensors to spot them, a quick enough workflow to track and engage them, and enough fire-power from suitable system (mainly a combination of high-enough rate of fire and heavy enough rounds that they stop them, such as heavy machine guns or auto-cannons).

Close to the bridge is also the space allocated for flagship-related tasks. This can function as the command facilities for an embarked flag officer with relevant staff, as the war room for the when Amiral Ronarc’h function as the regional ASW-lead, or as the planning space for embarked special forces. For special forces operations, the RIB-bay is built with space to handle larger (up to 9.5 meter in length) RIBs preferred by the French special forces, such as the Zodiac Milpro ECUME. The standard operating procedure is to lower the RIB with crew into the water alongside the frigate, and then give it enough line that it drifts aft until it is in line with the door found in the rear part of the hull just above the waterline, which facilitates easy transfer between the frigate and smaller vessels. One of the few details of the exterior of the Amiral Ronarc’h that still did not correspond to the final look is that the curtains for the RIB bays are still not installed. Once installed, these will not only help with signature reduction, but will also ensure that the conditions for anyone working on the embarked boats remain tolerable, regardless of whether it is hot or cold (or wet) outside.

Mounted high on the superstructure between the funnel and the mast you have two sets of launchers for a total of eight heavy anti-ship missiles. On the French and Greek frigates, these will be the latest MM40 Exocet, while on a potential Norwegian version the weapon would be NSM. A crucial detail is that the launchers are mounted low enough that the continuous side-plate covers them completely when looked at from the side – or from the level of a sea-skimming active radar-guided missile. In general, Naval Group sees stealth and signature reduction generally not so much as avoiding detection completely – modern sensors are simply too good and the work needed to reach that level of signature reduction isn’t cost effective – as it being a means of defeating incoming missiles and other weapons. You don’t need to disappear completely, just make sure that the chaff-cloud or other countermeasures is a more tempting target to anything approaching you with a seeker head and bad intentions. Eight heavy missiles is more less what is expected from a vessel this size, even if some recent ships have seen quite a bit heavier loads.

So having looked through the anti-air and surface-warfare capabilities, it’s time to look at the heart of the FDI – the anti-submarine warfare capabilities it is designed around. But that story is long enough to deserve its own post.