The HX fighter programme was a complex operation in which the Finnish Defence Forces spent years (and significant money) to find out which fighter and assorted package offered the best combat capability for a non-NATO Finland. With the question of Gripen for Canada in the headlines once more, and with both Rafale and Gripen seeing Letters of Intent from Ukraine, the Finnish experience has been used as an argument by all sides for a number of different points – some more grounded in reality than others. Having spent years covering the HX programme – and getting accused of hating or loving a different fighter every month throughout the campaign – I feel like it might be worth a few words to point out some of the things we learned in that competition.

(I am aware that some will find this post tilting a certain way, regardless of my attempt at sticking to stating particular items picked up during and after HX. If you want to read something that is written by the first person to fly the Gripen in its 39C form into combat, and something that is of a high standard but with an understandable slight pro-Gripen tilt, go and check out this article)

All five invited bidders made serious offers

It’s hard to overstate how significant this is. Taking part in this type of multi-year project is expensive. Very expensive. And while there certainly where favourites and underdogs, all five felt they had enough of a chance to warrant a serious effort (something which has not been the case in most competition before or since). None of the manufacturers also made any kind of formal complaints afterwards, again indicating that there were no perception of major issues with the process. All in all, this gives very high marks to the Finnish authorities, and adds weight to the results. At the same time, one should be careful to generalise as the Finnish set or requirements were rather particular.

The Finnish deal

The particularities included relatively free hands for the bidders to say how they would best use their respective fighter to protect Finland in an all-out war. The main framework was a set budget (both for procurement but also for operating the aircraft and for the weapons and spares they wanted to use, as well as for any infrastructure upgrades needed), that non-NATO allied Finland was to be able to operate the platform independently in all situations (which also called for some kind of technology transfer package to give the necessary know-how to Finnish industry), and the general expectation was that it should fit into some variant of the current Finnish Air Force CONOPS that include dispersed operations and a fleet of preferably 64 fighters.

The F-35 won

In the eventual evaluation, the Eurofighter and Rafale offers did not pass the obligatory gate checks to reach the evaluation stage. In the wargame-style evaluation measuring how well each package would support the Finnish Defence Forces in an all-out war, the F-35A offer won out. Second place was taken by the F/A-18E/F Super Hornet/EA-18G Growler combo, and in third came JAS 39E/F Gripen supported by two GlobalEye AEW&C platforms. The evaluation focused on a major war scenario, in which the air to air role was the focus (30%), with 10% weight being allocated to supporting the Finnish Navy, and 20% each to supporting the Army, long-range fires, and ISR. The aircraft were fighting with the support and weapons included in the packages offered, with the F-35A ranking first or joint-first in all mission sets.

You can draw a number of different conclusions from that, depending on your point of view. One is that the Growler really looks like it is a significant asset – as it likely was the differential that pushed the Super Hornet past the Gripen/GlobalEye-combination (unless you argue the Super Hornet offered either significantly better inherent capability compared to the JAS 39E, or alternatively was a lot cheaper to buy and/or operate compared to the Swedish delta, allowing for more spares and/or munitions in the Boeing offer). Another is that the F-35A is really impressive. In the evaluation, F-35A scored higher than JAS 39E/F backed by two world-class AEW&C platforms! The benefit of having the eye in the sky can hardly be overstated. Yes, Finland has a solid ground-based sensor network, and yes, the majority of missions were likely flown relatively close to the border, but the GlobalEye would still have been a huge asset, in particular when it comes to keeping an eye on what’s happening at lower levels, what’s happening at sea (including Lake Ladoga), and what movement patterns we are seeing on the ground. This result really was quite something.

The Gripen is really cheap

Did I mention the Gripen offer came with two GlobalEyes? Did I mention that operating costs where supposed to be similar? In other words – assuming that the need for weapons to fight a war with is roughly equal between the two, which seems a reasonable assumption to make – the difference in procurement and operating costs between 64 F-35A and 64 JAS 39E/F Gripen is significant enough that you can fit two large converted biz-jets crammed full of high-tech electronics and their spares into the difference in procurement costs. The operating cost of 64 Gripen is also so much lower compared to the operating cost of 64 F-35A, that you can fit flying the converted large biz-jets inside that difference, as well as training and employing tens of people to fly, maintain, and operate the AEW&C aircraft, and building the physical and information infrastructure needed for the operations. Gripen is dirt cheap, something that didn’t really come as a surprise, but the scale of the difference really is something.

Now, when I say “dirt cheap”, that is a relative term. The flight hour cost of Gripen is not a third or a fifth of the F-35. A Bombardier Global 6000 without the skibox on top costs below 15,000 EUR per hour to charter, which gives an indication of what we are talking about when you can fit two of those into the overall package. The major part of the operating costs for the Finnish Air Force would have come through everything surrounding it, and these are sums that are harder to estimate. If you would force me to make an estimate, I’d say the difference is in the 10-20 % range in a Finnish context (see below), probably closer to the upper boundary than to the lower*.

*This estimate (and I can’t stress that word enough) is based on a simple thought experiment where the GlobalEye has lower aircraft flight hour costs than a fighter, but you would need more operators from a non-existing training pipeline, more infrastructure, and generally more dedicated support, compared to putting in 6-12 more Gripens into the offer which would require more fighter pilots, a bit more spares and ground support, but all of these would benefit from economics of scale as you wouldn’t create any new needs but rather just increase the number of already existing resources

The F-35A isn’t too bad either

With that said, the operating costs calculated for the Finnish Air Force F-35A operations aren’t too bad either, but more or less in line with what we currently pay for the F/A-18C Hornet ones. I broke down some of the numbers and reasoning when the HX decision was announced, including getting comments from then brigadier general Keränen (now retired major general and former chief of the FinAF) regarding why certain Finnish numbers differ from Swiss or US ones. Head over to that post and scroll down to the “Money, Money, Money…”-section for the details.

The tl;dr version was that “At the end of the day, all bids had roughly similar annual operating costs”, which also had been a stated requirement.

Finland do not plan on making major changes to how we operate our air force

All bases remain in use, the aircraft will still see a lot of conscript roaming around doing maintenance work, dispersed operations (including from road bases) are still a major theme, and so forth. This is in fact not overly different from the US Agile Combat Employment concept (ACE), which has seen some interesting exercises in particular in the Pacific theatre test out how things could be done (there is a post where I discuss that as well). For our Swedish readers, you might note that there are some differences between the Swedish Bas 60/90-concept and the Finnish dispersed basing concept, in particular regarding how small you want your road bases to be, and with the Finnish aircraft generally moving around more, which might also be worth keeping in mind. Not all road bases are created equal, but then the idea isn’t to create as miserable base as possible either.

Fully sovereign operations

A major question surrounding the deal was whether Finland was able to operate the aircraft independently, as Finland was not a NATO-ally and as such could not count on US (or Swedish/British/German/French) support in a war. As such, the Finnish F-35 operations are set up so that -when it comes to spares, critical systems, maintenance capability, and so forth – these are to be found in-country and under Finnish control. I am fully aware that a number of NATO countries have opted for other alternatives in the name of optimisation and potential savings, and these are without doubt being studied in Finland as well now that we are full members of the alliance and as such are supposed to be able to trust each others, but it is worth noting that this was the setup asked for and received as part of the original order.

Now, with the US sliding towards authoritarianism and further away from traditional transatlanticism, it does change the equation when it comes to the F-35 to some extent. It changes a lot of things and assumptions to be frank, and I don’t necessarily see all of this going away when Trump leaves office. Coming from a country that has seen exactly how ugly polarisation in a society can get, I sincerely hope the trend is broken, but for the time being that is not something that we can count upon.

With regards to the F-35, the one key part is the updates to mission data which can be crucial to get done quickly during a conflict, and where active opposition by the US administration might cause real issues. Still, of all the things related to current trends in the US, F-35 is not on my Top-10 list of things to worry about. To begin with, Finland is far from the only country thinking about this particular issue. Let’s remember that Lockheed Martin (and their partners) really likes their market share and will fight tooth and nail for their products not being seen as a potential liability, as will any number of decent politicians still left. Additionally – for the really cynical among us – with the breakdown in the rule of law (including international treaties) in the US and the corresponding shift towards transactionalism, you might find that this actually opens up new possibilities. They might just come with some “additional costs”.

Is that ideal? No, far from it, but it’s good enough that I’m not losing sleep over it.

The export success of Gripen is ambiguous

The Gripen in its latest version is having a somewhat ambiguous result sheet on the export market. The fighter has scored a few deals and seem set to bag a few more, which is an impressive feat on a relatively crowded market where the US is still offering three-four different fast jets, Rafale and Eurofighter are both looking strong, and in addition the Chinese are finding new markets on a scale we haven’t seen since the Chengdu J-7 (NATO reporting name: ALMOST-FISHBED). Still, once you start looking at the threat picture of the countries interested in the JAS 39E Gripen, it’s not like it is a club of highly ambitious air forces fearing a fight with neighbours operating late-mark Flankers. Colombias 17 new Gripens will the second they arrive become the most modern fighters in that part of the world, faced with such possible opposition as first-generation Mirage 2000P in Peru and the handful of operational Su-30MK2 in Venezuela, while the recent 2025 Cambodian–Thai border crisis saw Cambodia struggle to get a single MiG-21Bis airborne from the twenty or so retired airframes stored.

At the same time, the Arexis EW sensor suite which sits at the heart of some of the reportedly most impressive capabilities of the JAS 39E-version has been chosen to form the basis for the German dedicated SEAD/DEAD-version of the Eurofighter, the Eurofighter EK, that will replace the Tornado ECR as the sole European dedicated tactical SEAD-platforms. If getting picked as the best option to beat down a third-rate air force might not be the vote of confidence NATO air forces are looking for when searching for references for their new fighters, Germany picking its EW-suite as the basis for their upgrade on the other hand certainly is exactly the kind of vote of confidence you are looking for.

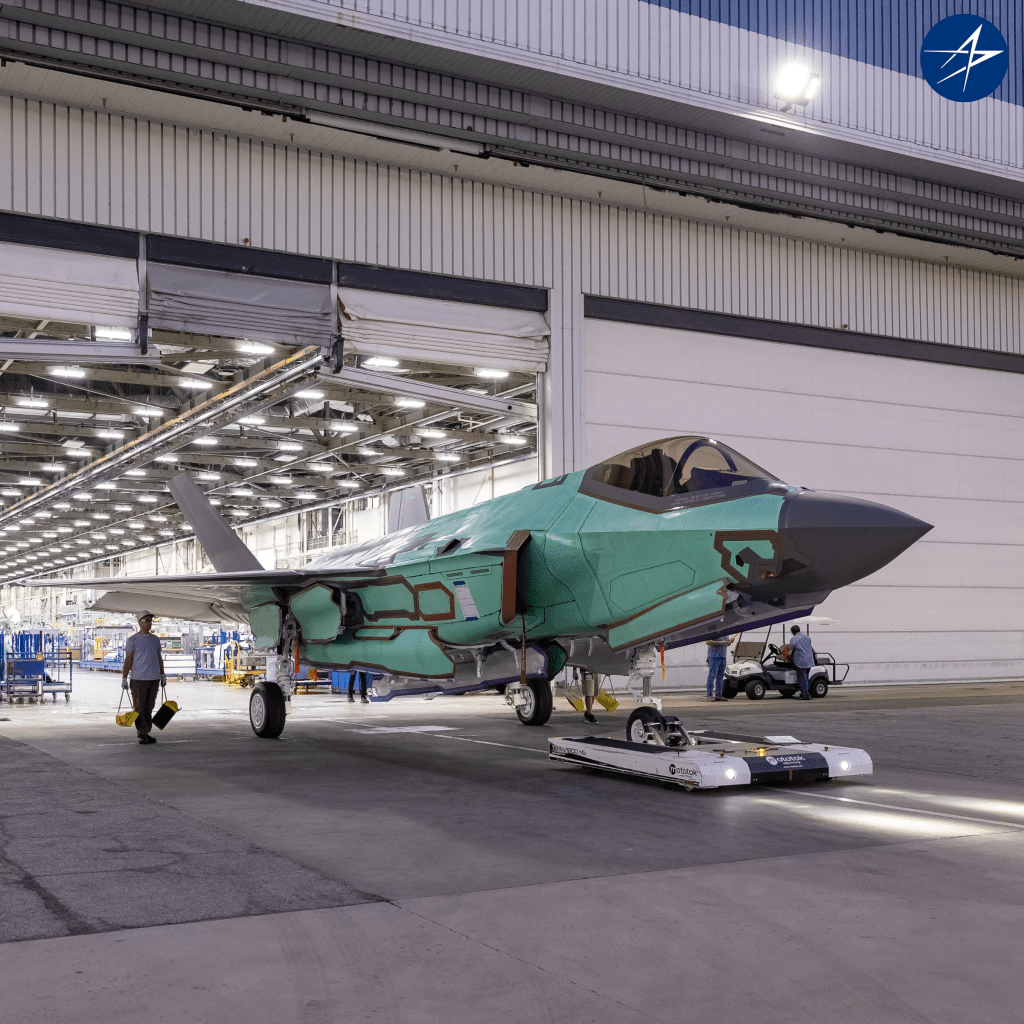

The Block 4 upgrade really is turning into something of a headache

The Finnish timeline lined up rather well with the Block 4 upgrade, with the first aircraft coming in Lot 17 and the rest a bit later. Unfortunately, the delays to Block 4 raises a lot of questions, and the answers to some of these are that the aircraft will come into service with less capabilities than envisioned in 2021. With that said, the F-35 in its current configuration is a combat capable aircraft, as evident by the fact that it has indeed taken part in combat missions since 2018 and onwards, in a number of different versions and parts of the world.

(Yes, there is a story going around from someone who frankly should know better, stating that the F-35 “are lacking qualified software modes essential for combat”, at a time when current F-35As are flying traditional SEAD-missions into Iran according to the time-honoured “first in-last out” adage in the escort of B-2s. Yes, the Iranian air defences were degraded by then, in part because Israeli F-35Is had already reportedly been there – they aren’t releasing details – but the F-35A is very much flying into harms way and doing the job it is asked to do already today Edit: I didn’t read it carefully enough. As pointed out by Sweetman, the “lacking essential”-piece referred to the current deliveries and not the existing TR-2 / Block 3 aircraft. Sorry about that!)

The main issue with the Block 4 delays is not the software part, but rather TR-3. TR-3 is in essence can be described as the hardware part of Block 4, and these issues – including the expected engine upgrade – are what can become really expensive upgrades in the future if the aircraft are delivered in a state where you need to do deeper changes to install TR-3 at a later stage.

(In practice both TR-3 and Block 4 are made up of a number of different building blocks, not all of which arrive at the same time, and the list of which features are included have changed over time, both seeing things added and taken away, so this isn’t as binary as one might imagine)

Exactly how expensive your F-35A upgrades are depends a lot on when exactly your aircraft were produced, with early adopters already having done a number of upgrades, and the longer you wait the more capability will you have rolling of the production line, meaning that while this is a headache for Finland, for anyone placing a major F-35 order now or in 2030 your mileage may will vary.

Neither is ‘The Best’ aircraft

That F-35 won in Finland is a nice reference for the aircraft, and as a Finnish reservist and tax payer I am very happy with that.

That does not mean the aircraft is the ideal fighter for everyone everywhere.

The F-35 has a number of really nice features. The huge engine is nice, not only as it gives the aircraft speed forward, but as a source of power for numerous systems, including the radar which is another great feature. EW-systems are notoriously difficult to compare, but everything indicates that BAES has hit a home run with this one. There’s certainly also a benefit in being part of a huge user group, both when it comes to synergies and economics of scale, but also as mentioned if the users need to put a bit of pressure on the supplier at some point.

Gripen in and by itself is cheaper, and while being part of a large user group is nice when sharing non-recurring costs, being a major operator in a smaller group means your voice carries more weight when deciding roadmaps and upgrade paths. It is also difficult not to feel the Meteor missile is a mature weapon for those days you want to go that little bit extra. At the same time, late-mark AMRAAMs have made some impressive strides when it comes to range – even if the difference in propulsion always will be felt. Comparisons to AIM-260 JATM are a bit early to start making, in particular as there are still open questions regarding export permissions and costs, so for now the Meteor is still a difference maker.

(We all know that what we really would like to see is an F-35A with an underwing AIM-174B Gunslinger, just because of the outrageous nature of the missile)

I have no idea what would make sense for Canada

My understanding of the needs for the Royal Canadian Air Force isn’t good enough that I’d be ready to say which way they should go.

(This might not come as a surprise to long-time readers, as during HX I wasn’t ready to say what Finland should buy, and that is for an air force I knew quite a bit better, and in a very familiar overall context)

But if I’ll spend a few minutes describing how I might see the Canadian need for fighters, it might answer some questions. In essence Canada has two very distinct use cases. One is defence against enemy aircraft, missiles, and ships close to the homeland. As the distances are vast, you aren’t really looking for a dogfighter, but rather something with a lot of range and as many missiles as possible (the irony here is that the Super Hornet which was coming to Canada as an interim fighter until Boeing’s civilian business decided it wanted to pick a fight with Bombardier would be a really nice fit), as the main missions will be to spend hours chasing swarms of cruise missiles or keeping an eye on vessels moving in places Canada would prefer they don’t. Here the need for any kind of air-to-air combat is somewhat limited, as even long-ranged beasts such as the MiG-31 would struggle to make more than the occasional appearance (and in those cases, Norwegian F-35As with AIM-147B hunting their tankers would be a really interesting ally to have). The preferred platform would be a relatively large long-range interceptor, but to be fair this is more a question of logistics, operating and weapons costs, and number of airframes available, than outright performance on any individual fighter.

The other mission is to deploy to Europe, where a RCAF unit would operate as part of the overall NATO effort against a Russian aggression. Here, it is hard not to notice the fact that this is a scenario a large number of countries have looked at and said “Yeah, the F-35 is the answer”. You can make an argument about politics having influenced these decision in some (or all) cases, and that the political argument falls the other way for Canada today. However, regardless of to what extent that is a solid argument, it is clear that if you fly a detachment of F-35A to Europe, you will have an easier time finding a partner air force with which to integrate with compared to finding a JAS 39E Gripen operator. On the other hand, Sweden sits in a really nice location for Canada to be able to take responsibility for supporting the Canadian multinational brigade in Latvia, though granted Poland, Denmark, or Germany does so as well.

Both aircraft are able to perform in both roles, and while you see some nonsense about F-35A not being able to operate in the Arctic, those are just nonsense. The F-35 has happily been operating in Alaska and Northern Norway for years already, and in particular the operations in Norway seems to have impressed the Finnish Air Force when thinking about which aircraft should defend Santa Claus (whose village is literally five minutes down the road from our upcoming first F-35 wing).

There is obviously a political side of things – both an international relations part and a domestic political aspect – but there are more knowledgeable people when it comes to those, and I don’t feel covering HX has given me any particular insights that are applicable to Canadian industrial policy.

What about Rafale?

Rafale, besides being the best-looking current fighter jet, offer some really interesting benefits, while also having some compromises which you would have to live with. Perhaps the most important change since 2021 is that France has considerably increased their trust in country’s politics X conventional military capability X nuclear weapons = benefit of being their friend-score (or rather, the US and UK are doing their best to not compete any more), and with FCAS being on the verge of scrapping, the case for France being ready to invest a lot in the future development of the Rafale over the next decades looks good. This is a good aircraft, with the backing of a solid partner. Just be aware that you can choose between getting the upgrades you want (and pay for them), or get upgrades France wants (and split the bill). Is that better or worse than the situation you find yourself in as a Gripen or F-35A operator? Probably not, the options are just different.

As such, it is an obvious place for Ukraine to look, though crucially both the Gripen and Rafale LoIs suffering from the tiny detail of there being no funding for either Ukrainian JAS 39E/Fs or Rafales. I am fully aware of Ukraine having expressed an interest in both aircraft, but with there being money for neither and the envisioned 250-strong fighter fleet looking extremely unlikely, in reality we are likely to a see a fleet dominated by one or the other (go check up the numbers, there aren’t many regional powers even in hostile neighbourhoods operating anything close to 250 modern fighters, and most of the handful who do have built up their forces over decades while not simultaneously having to rebuild their country after years of war). If I would have to guess, my guess is that Ukraine would be happy with either Rafale or Gripen – as both would be significant steps up in capability over their current equipment – and they are going to take whichever aircraft first is able to secure funding. Getting France to lean on Belgium for a release of the Russian frozen assets because it would mean an export deal for a 100 Rafale is probably a quite good move politically.

Now, this is a medium- to long-term plan, and in the meantime I wouldn’t be surprised to see more Mirage 2000 and possibly the discussed JAS 39C/D transfer within the next year. Both provide solid capabilities, and if the Meteor would be made available (which is doubtful) then JAS 39C could be the aircraft to take the fight to the Russians. Otherwise both are good options for chasing the cruise missiles and long-range one-way attack drones we are seeing over Ukraine.

One of the few potential benefits one way or the other between Rafale and Gripen in Ukraine is that the Brazilians plans to integrate the datalink of the Gripen with their A-29 Super Tucano-fleet with the purpose of using Gripen’s air-to-air sensors to direct the slower aircraft to intercept slow-flying aircraft of drug smugglers and then deal with them with their wing-mounted .50 cals. If (and that word does a lot of heavy lifting) Brazil would be happy to export the aircraft to Ukraine, the Gripen/Super Tucano combination – in particular when backed up by the ASC 890 AEW&C – would be an excellent low-cost Shahed-hunting concept, possibly with the integration of low-cost guided rockets or similar.

From a Ukrainian point of view, between Rafale and JAS 39E/F Gripen, there really isn’t much of a difference in performance, regardless of what people on the internet would want to claim. Both are good, and both are largely as good (or bad) as the support and weapons packages they come with. Both can sling cruise missiles, have a good assortment of air-to-air weaponry, and can also do maritime strike. Just don’t expect an order for a 100 of each within the next months or so.