Long relegated to the sphere of thrillers and April Fool’s jokes – some rather good ones – the question of nuclear weapons in the Nordics have become the topic of somewhat serious discussion. And when our Minister of Defence has said that a discussion is needed regarding “new arrangements”, I feel it is my responsibility as a Finn to do my part. So here we go.

As so often is the case with these issues, the interest in the topic has has grown first gradually following the realisation of the undeniable role nuclear weapons play in modern hard security and diplomacy, and then suddenly with the increasingly aggressive stance of the current US administration. However, as can be expected for a topic that traditionally has not been high on the agenda, much of the public discussion is simplified to a “Bomb good, gives deterrence” against “Bomb expensive, illegal, and amoral” argument, which (besides the question of morality, which is subjective) while technically correct isn’t helpful for decisionmaking. Because while it is easy to just look at nukes as a binary choice, the decision on whether or not to acquire nuclear weapons is just part of the equation, and for the decision to be based on any kind of deeper analysis, you have to start with defining what is it that a new nuclear power in the Nordics (or Europe more generally) would want to achieve, and how they would use nuclear weapons (or the threat of them) to achieve the desired effect. You need a doctrine, and the resources to make that doctrine achievable.

In this post I will look at the extreme case of a new European nuclear weapon state emerging with domestically controlled weapons. There are a number of other options, such as (in reality French) extended deterrence, forward basing of assets and weapons, and even nuclear sharing along the lines of what the US currently does, which all are relevant (and significantly simpler and faster) options. See e.g. this thread by Tertrais if that is what you are looking for.

Many people not spending their days thinking about national security will associate nuclear weapons with mutually assured destruction. We have enough nukes to destroy your whole country, and you have enough nukes to destroy our, so we decide not to nuke each other. In the simplest of terms this leads to people counting warheads and finding that if the Russians have 4,380 warheads operational, we want to have a similar number to have parity. This comparison can then be made more multifaceted by breaking down the weapons the Russians have to ensure that we have similar ones. In other words, if Russia has tactical nuclear weapons (“battlefield nukes”), we want to have those as well to be able to match them step for step on the escalation ladder. Here is also where you usually get involved in the idea of a triad, with ground-based systems (offering survivability, size, and range), air-launched systems (offering flexibility and being relatively cheap), and submarine-launched systems (being extremely survivable and ideal for a second-strike capability). However, it is not always recognised that by saying you need to have (smaller) copy of the arsenal of the superpowers to have a viable deterrent against one, you are already making several assumptions that aren’t uncontroversial. These are easy to make, but fail to recognise most nuclear powers do in fact not have triads or thousands of nukes, but rather have adopted a number of different strategies, arsenals, and postures, to meet the unique security challenges which were what caused them to decide they needed the ultimate tool of destruction available to mankind (that might in fact be biological weapons, but let’s not make things more complex than they already are). Mutually assured destruction is a doctrinal idea for superpowers, and in the same way that you can have a navy without believing you need half a dozen carrier strike groups, you can have nuclear weapons without having thousands of warheads in a giant triad.

The current issue facing the Nordics is that Russia has nuclear weapons, and isn’t afraid to use them to their advantage, including in Ukraine. Now, ‘use nuclear weapons’ doesn’t necessary mean detonating them, as it is clear that Russia used the fear of a nuclear exchange to great effect in 2022 as part of their war effort to put pressure on Washington. The capability to actually fire nukes on their enemies also provide Russia with leverage in a crisis or war that non-nuclear weapon states don’t posses, as regardless of how eager a country like Poland might be to respond to Russian pressure by either escalating or by matching Russian steps on the escalatory ladder, there is always the knowledge that at some point you will run out of steps on your ladder, while your adversary can continue climibing. In addition, there is the knowledge that any crisis involving nuclear states will draw more attention internationally from the superpowers (see: India and Pakistan) than a crisis where the risk of nuclear exchange is small or non-existent.

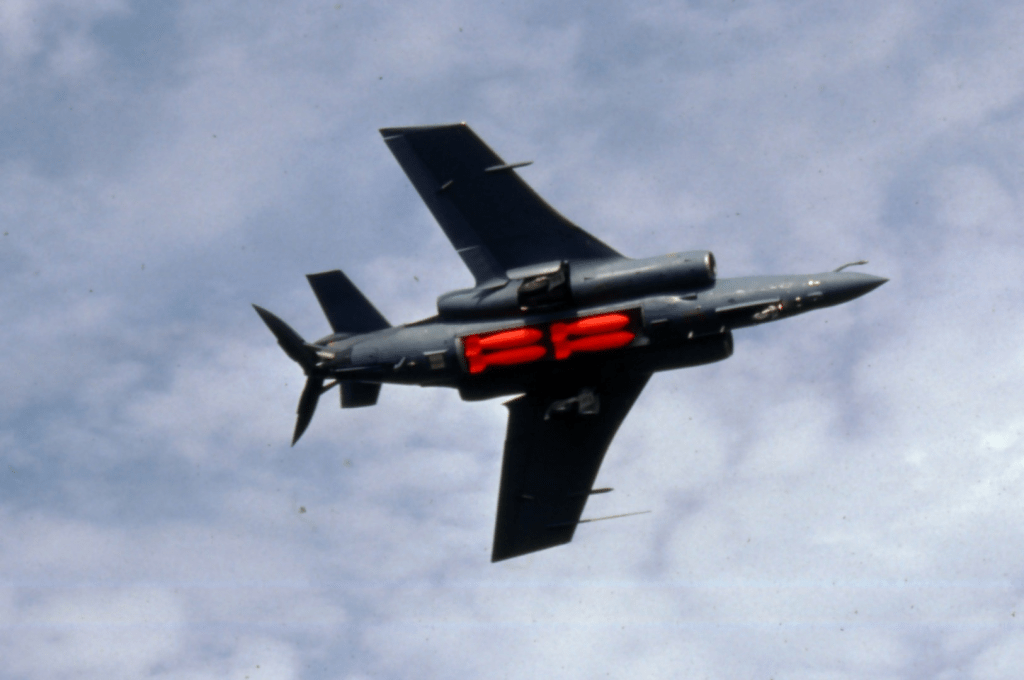

This last part is one of the key points, as quite a few countries have adopted postures where they control a limited number of nuclear weapons, and instead of detonating them their purpose is to ensure that a friendly superpower won’t let them get into such a bad place that they might have to use them. A key example was the early Israeli nuclear arsenal, where it was used successfully in the early parts of the Yom Kippur War of 1973 to ensure that the US both aided with rearming the Israelis and replacing their losses, as well as ensuring Washington kept up the pressure on Moscow to try and get their clients to not do anything overly stupid. This was done through “conducting operational checks on delivery vehicles in a manner that was easily detectible only to U.S. intelligence, signaling that it was considering unsheathing its opaque nuclear weapons capability”, as Vipin Narang describes it. Another country looking to do the same was the South Africans, the whole arsenal of which consisted of a grand total of six bombs (the ‘device’ codenamed Melba which was extremely crude, but could have been rolled off a cargo plane to create a big boom, a proper gravity bomb code-named 306, and four Hamerkop glide-bombs based on the Raptor I). For the aviation geeks out there, yes, the Blackburn Buccaneer was the nuclear bomber of choice, meaning all three services that operated it planned for its use in both conventional and nuclear roles. A seventh weapon was under construction when the whole programme was disbanded in 1990.

The South African case is extreme, but shows that not all nuclear arsenals look the same.

So which weapons would a European domestic nuclear power need? The British answer is you can make do with ‘just’ a solid second-strike capability on a number of submarines, as being able to rain down nuclear warheads on the enemy should deter the enemy from doing the same (and, crucially, NATO has tactical nuclear weapons in the form of the US ones, though that is part of the problem these days). However, as was rather spectacularly displayed in The Wargame – the Sky and Tortoise podcast I had the great pleasure of being a small part of last year – this does leave questions open with regards to the flexibility. Yes, you can use a single Trident from a Vanguard-class submarine to reduce Severomorsk or one of the air bases used by Russia’s long-range aviation to a smoking ruin, but that will tell the Russians roughly where your boat sits, runs a real risk of being mistaken for the opening salvo of an all-out nuclear exchange, and now your boat is down from sixteen from fifteen missiles available for the rest of the war. All in all, it might not be the ideal tool to escalate in a controlled manner.

The French has a somewhat different answer. Back in the late 50’s France had just gotten a few harsh lessons in the fact that what Paris saw as vital national interests might not always align with what Washington saw as vital national interests. One of the key lessons here was the Suez Campaign of 1956, where the UK and France together found out that the US was less than pleased with their actions (the other was Indochina). But while the UK drew one lesson and decided to align itself closer to the US, France, to again borrow a quote from Narang, lacked two things that meant it decided against following the example of the UK: “an historical special relationship with Washington, and the English Channel”. The French doctrine has changed over the years, but at the heart of it lies the idea that a fully independent force de dissuasion gives France the option to decide for itself when things are bad enough that they need to start nuking people (this is a huge oversimplification, but an interesting detail is that of the nuclear weapon states, France – together with North Korea – is the only one to have experienced foreign troops overrunning their capital in living memory, meaning that it does feel like instead of theoretical discussions about red lines the French threshold for nuclear use largely comes down to “See that picture of Nazis marching through Paris? We don’t want that again, if something like that is about to happen, we’ll drop the nukes”, which to be honest has its benefits as a theoretical framework).

This more pragmatic approach to the question of when and how to use nuclear weapons creates a need for a bit of flexibility, and as such the French nuclear arsenal include smaller nukes as well – though crucially they are not called ‘tactical’ nuclear weapons as there is a strongly held view that any nuke will have a strategic effect and not just a tactical one. This is seen e.g. in the air force-branch responsible for using the Rafale on nuclear-strike mission with the ASMPA-R cruise missile being the Forces Aériennes Stratégiques (FAS), which can be contrasted to the traditional US naming conventions regarding strategic bombers and tactical fighter-bombers. The three legs of the French deterrence force is the ballistic missile submarines, as well as the Rafales of the Air Force and those of the naval aviation and the carrier Charles de Gaulle. Interestingly, the French had a ground-based component into the 1990’s with silo-based IRBMs and mobile shorter-ranged systems, and is now looking at reacquiring theatre ballistic missiles (~2,000 km range) in the form of a conventionally-tipped mobile weapon. The Missile Balistique Terrestre (with the for English readers rather confusing abbreviation MBT) is still only in the development stage, but is interesting in that it is yet another data point when it comes to the proliferation of heavy ballistic missiles for conventional strike, while it obviously also could serve as the platform for a nuclear-tipped weapon if the decision was reversed.

I am not completely convinced by the argument that a Nordic nuclear weapon state absolutely must have a tactical nuclear weapon, but in most cases it likely would help with providing more tools to the politicians compared to ‘just’ having a strategic capability. Neither am I absolutely convinced a submarine-branch would be absolutely necessary, but again it could help. As alluded to in the beginning, the doctrine of a Nordic nuclear force needs to be developed first, and then matched to a suitable arsenal. We won’t match the Russian arsenal weapon for weapon, but can we deter Russian nuclear weapon use by having an arsenal strong enough that we can match their steps on the escalation ladder until they have devastated our whole country? This requirement of total destructive potential compared to one’s own country – obviously somewhat open to discussion how exactly you measure it – has been used by a number of a smaller nuclear powers. The assumption is that Russia should know that while Russia might be able to survive a nuclear war with an opponent that would not, it would still be a zero-sum game for Moscow as the gains (devastation caused) and losses (devastation received) would balance out.

Side-note: nuclear doctrines are a grim topic, but so is war generally.

You can also make a more general case without directly comparing numbers, where you just want to reach a certain threshold of (potential) damage where Russia should draw the conclusion that the level of damage is unacceptable relative to the potential benefits. For the Nordics, a particular angle of this is the Murmansk-region, which hold a key role as the basing area for the better part of Russia’s second-strike capability. Such a Northern-fleet focused doctrine could possibly – I’ll let the true wonks debate the realism of it – allow for an asymmetric counterforce strategy where a relatively limited number of weapons could hold a disproportionate part of the Russian nuclear arsenal at risk, with the aim of creating fears in Moscow about the ability of the surviving Russian nuclear assets to deter not the rest of Europe, but whether it could maintain parity with the US arsenal following a limited exchange with a European adversary.

Another option is the South African route, where the plan is simply that if things start looking bad, the US (and other allies sitting on the fence) should know that this can escalate into a nuclear exchange, which should then compel them to throw their weight weight behind us to ensure that we never need to actually start flinging nuclear weapons across the border.

Now, a major question is could a Nordic country build a nuclear weapon? The answer is ‘Yes, but…’

Nuclear weapons are complex, but it’s not like they are cutting edge. The basics are after all something humanity mastered in the 1940’s, without the computing power and manufacturing tools available to modern society (and as a mechanical engineer, let me tell you that making complex things is vastly easier now than in the 1940’s). One key issue is the raw material. Sweden has natural uranium, and when they were looking the possibility of building a bomb one of the key ideas was the ability to use domestically mined uranium in their own reactors to then produce plutonium. This turned out to be difficult, so today the best option would probably be to call Urenco and ask how much they’ll charge for a suitably sized batch of weapons grade HEU?

This call would obviously lead to some, eh… interesting, discussions with the governments of the countries involved in Urenco, which rapidly leads us to the question of which countries would be willing to openly assist Nordic countries acquiring a nuke, which countries may do so covertly, and which would be ready to turn a blind eye. Also note that it isn’t enough for the country wanting the bomb to secede from the Non-Proliferation Treaty claiming that extraordinary events have jeopardized its supreme interests (which is literally how the process goes), but any country offering direct help would also have to secede in order to be able to openly “in any way to assist, encourage, or induce any non-nuclear weapon State to manufacture or otherwise acquire nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices, or control over such weapons or explosive devices”.

For the bomb technology itself, Sweden is probably the European non-nuclear weapon state that could become one the fastest. This is largely down to the Swedish nuclear weapons programme of the 1950’s and early 1960’s, which was quite well advanced. A demonstrator device might have been ready by 1964 and “no further research was really necessary after 1961-1962” if the final green light would have come, but by this time the weapons programme was officially on hold and the research done by FOA was more or less secret (and possibly with less political support than an active nuclear weapons programme in a democracy is supposed to enjoy). Still, a US NIE in 1966 estimated that Sweden could produce a nuclear weapon “two years after a decision to undertake a program,” though other “estimates varied from two to seven years“. The researchers involved had among other things conducted implosion testing, and were confident in their ability to create a working bomb without the need for full-scale testing (which is a not unimportant question, as otherwise you need to both scrap the NPT and the CTBT). How much of this know-how is retained in today’s FOI is anyone’s guess, but at the same time the tools and information available from other sources to someone who would be put in charge of a Folkhemsbomb would today be at another level completely than they were in 1960.

Then we come to the question of delivery systems. Long-range precision fires from all domains is more or less in the toolbox of every serious defence force these days, and the required technology to put a tactical nuke on its target with a cruise missile or a short-range ballistic missile isn’t really an issue. Fun fact related to the Swedish case is that while the history of Swedish computer pioneer Datasaab often is mentioned as going back to the CK 37 of the Viggen, the original Swedish transistor computer was in fact an offshoot of the (cancelled) RB 330 surface-to-surface nuclear-tipped missile with a 300 kg tactical charge and the range to reach the ports on the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea. The domestic missile projects RB 340 and RB 370 and the US IM-99 Bomarc were also studied as potential surface-to-surface missiles, while both A 32 Lansen and AJ 37 Viggen had the ability to be modified to be dual-capable, while the heavier dedicated Saab A 36 strike aircraft was projected but eventually cancelled.

There is little doubt that e.g. both Saab and Kongsberg sit on the required know-how to develop a cruise missile that could transport a nuke to its target. However, the project would not be cheap. The allocation for funds to the development of the ASN4G cruise missile which will replace the ASMPA-R as the nuclear cruise missile of the Rafale by 2035 got allocated 3 Bn Euros. In other words, the funds already allocated to the project equals the total cost of the Finnish Navy’s Pohjanmaa-class programme. If we look at more complex delivery systems, the first generation of the M51 submarine-launched ballistic missile cost approximately 5 Bn Euros in research and development, with an additional 3 Bn Euros in production cost, which adjusted for inflation lands us at something like 11 Bn Euro in total. Or, roughly on scale with the HX-fighter programme. However, here it should be noted that France through half a century of ballistic missile development and ArianeGroup has a domestic development and production infrastructure in place that none of the Nordics even dream about as things stand currently. The MBT which we mentioned earlier is perhaps a closer comparison to what a Nordic ballistic missile would look like, and here the development budget for a conventionally-tipped road-mobile MRBM with 2,000 km range is set at approximately 1 Bn Euros, for this stage. Quite a bit less than the SLBM, but again it should be stressed that development is not the same as “cost for an operationally fielded weapon”, so expect a larger sum before we see any large trucks with missiles running around in the Massif Central (and again, France has ArianeGroup, the Nordics do not). Submarine operators Sweden and Norway could certainly field a tube-launched cruise missile, to give some kind of a second-strike capability – again, see the (probable) Israeli capabilities as well as those of Pakistan.

Let’s do a quick calculation: 3.5 % of GDP is 17.5 Bn Euro for Denmark, 11.7 Bn Euro for Finland, 24.9 Bn Euro for Sweden, 19.2 Bn Euro for Norway, and 38.9 Bn Euro for Poland. As such, developing a domestic delivery system is certainly doable, in particular if you find a suitable international partner that is happy to cooperate with you – either in the shadows or openly under the classic cover stories of creating a domestic space launch vehicle. Besides ArianeGroup, there are a number of possible partners. Ukraine has quite a bit of knowledge left from their days as a key part of the Soviet WMD delivery ecosystem, South Korea has developed the huge Hyunmoo-5 domestically, while Israel might also be willing to share their know-how. However, what is worth remembering is that delivery systems is just one part of the equation. You really want somewhere to store and maintain your weapons, and a proper base costs money. Then you want to protect your nice base, with both the UK and France having dedicated battalions – the 43 Commando and Morsier Marine Rifle Battalion respectively – of hundreds of marines for base protection of their SSBNs. But it doesn’t stop there, you also need a proper command and control setup, which usually means a dedicated tailored high-security system which again needs development resources as well as continuous maintenance and upgrades to be trustworthy. The development of the nukes themselves is also a massive undertaking, starting with the creation of the facilities and the research and development tools needed (unsurprisingly, while commercial tools are very good these days, certain simulation and development tools would almost certainly have to be dedicated products), and then moving on to production. In the case of the UK, the annual cost of the nuclear deterrent – which as mentioned is limited to a single (if very expensive) system in the form of the nuclear ballistic missile submarines – the total annual operating budget including maintaining the weapons, bases, and disposal represent approximately 6 % of the total defence budget, or around 3.5 Bn Euro annually. However, the UK is currently in the midst of a modernisation programme that includes new submarines as well as upgrades to both missiles and warheads, meaning that to the 3.5 Bn Euro running account should be added what is described as a ten-year long programme costing approximately 150 Bn Euro. In other words, even if the four Nordic countries and Poland reached the 3.5 % target, the UK replacement programme would eat up 13.4 % of their combined annual defence budgets for the next ten years, while the annual costs of running the UK deterrent would be roughly 3 % of their combined annual defence budgets. And again, the UK leans heavily on existing industry and infrastructure, as well as cooperating closely with the US.

Everything can be solved, and it is not unreasonable to think that with one of the prerequisites of a Nordic nuke being that the country would not become a pariah within European NATO, more technology than anyone would care to admit might be available for purchase from friendly nations, in particular as long as they officially are meant for something else (the Finnish naval mining platforms certainly need secure comms in the form of a nice new French system, I am sure we can all agree. And Sweden’s space ambitions could definitely use a domestic space launch vehicle incorporating foreign design assistance). However, France and the UK being happy to accept more European nuclear weapons should not be thought of as a given. For the recognised nuclear weapon states, their default policy throughout the decades have been one of non-proliferation as that has been felt to promote the stability status-quo powers prefer, while also ensuring that their status as nuclear powers remain as exclusive as possible with the benefits it provide. Since the NPT proved to be – despite a few high-profile failures – largely successful in containing the spread of nuclear weapons, there has also been a fear that proliferation is a row of dominoes just waiting to fall, where new nuclear weapons states would set in motion a chain reaction of their adversaries and rivals wanting the bomb as well. Now, you can make an argument that covert assistance has been provided before to emerging powers (in particular Israel, though notable is the timeline of when their programme kicked off and when the NPT entered into force and eventually became the recognised norm), and you can also argue that since none of the current second-rank nuclear weapon states (with the exception of China) can even dream about reaching parity with the two top dogs, teaming up with other friendly European countries might still be the preferable option for in particular Paris if things continue down the current track. But we are not there yet (at least not based on how it looks from the outside).

However, let’s get back to the cost. Even in the best case with some assistance being offered and the old folders of the Swedish nuclear weapons programme being found in some basement of FOI and dusted off, a handful of weapons and a delivery system or two will be an investment in the range of tens of billions of euros, likely in excess of 100 Bn Euro in total. That’s not impossible if it is identified as a national priority – Sweden is currently at least officially entertaining the idea of developing their own sixth generation fighter which likely would be of similar size, and which I called “extremely difficult to imagine” – and in particular if you accept it will take a few years and not try to speedrun the bomb it might be doable. But it would be a sizeable chunk of the defence budget of any Nordic country. In other words, how many armoured brigades or fighter squadrons are you ready to give up in order to have a nuclear deterrent? I’m not saying it is wrong to trade one for the other – you might make a good argument that the deterrence effect of nuclear weapons is outsized compared to conventional arms – but the harsh realities of what is given up needs to be accounted for. And if the answer is an expanded defence budget, we all know those funds need to come from somewhere else. Sure one can go down the Pakistani route where prime minister Bhutto declared a readiness to have the country “eat grass, even go hungry” if that was what it took to get the bomb, but I don’t see that being desirable or even an option in the Nordics. Nordic cooperation may obviously cut the costs, in particular as the individual countries have certain areas of expertise that would be handy to pool. One option is for a purely joint Nordic nuclear weapon force developed and fielded jointly, under rotating command as envisioned in this piece by Johannes Kibsgaard. That is a bit too radical even for me, though I certainly appreciate the outside-the-box thinking, and the deterrence effects of never knowing who is the one deciding on launches and targeting is probably worth studying in more detail. However, a joint development of the warhead, simulation environments, communications, and delivery systems, would bring huge savings, even in the case of the operational systems and warheads being operational as purely national assets under national command and control. This could be doable, as long as we Finns sitting furthest to the east are comfortable with the possibility of Sweden deciding to nuke Rovaniemi airport in case the Russian armoured spearheads ever break through.

So should we try and sprint for a nuclear weapon? I still find it hard to see such a scenario, considering the costs in both resources and diplomatic reputation, coupled with the technical challenges and lack of suitable raw material in the Nordic countries. However, that it even is discussed is a – for the lack of a better word – interesting development, that needs to be taken serious (the worst option is a kneejerk reaction to some major event where the population and politicians react to a major change by demanding nuclear weapons, and only later start to think through things – see our Article 5 commitments which some apparently only now realise works both ways…).

There would however be a value in starting to hedge our bets, in other words start to take steps looking into what a Nordic nuclear weapon would look like, how it would be developed and operationalised, and crucially what would be the doctrine behind it. This would create two obvious benefits: 1) if things change and we suddenly need a weapon, we know where to start, and 2) most crucially it can be used for leverage vis-a-vis the current nuclear weapon states to get them to accept nuclear sharing agreements and reinforced extended deterrence in exchange for not taking certain steps towards setting up a domestic capability. This was used successfully by West Germany to achieve a very favourable arrangement relative to US weapons in the early parts of the Cold War, and as mentioned nuclear weapon states tend to prefer these kinds of arrangements if the alternative is outright proliferation.

It is worth remembering a lot of deterrence can be achieved through conventional means – the Russians seem very afraid of the kind of massed conventional precision fires that the US has perfected – and also that cyber open up new opportunities to do potentially devastating things at a significantly more limited cost. However, cyber is of somewhat limited value in deterrence as the best cyber weapons often can be described as one-shot ones as once you use it you will alert the adversary to that particular issue, and hence they are difficult to use for signaling or for gradually stepping up the escalation ladder. The psychological effect of nuclear weapons also means that they do – right or wrong – occupy a particular slot in the minds of decisionmakers on both sides of the border, so while the devastating effect might be achieved in other ways, the question is if their deterrent effects can be?

Which leads us back to where we started: can we count on friends providing that effect, or do we need our very own ones?