The preliminary request for quotations for the HX-program is now out, and the process is kicking into the next gear. The manufacturers will have about three-quarters of a year from when it was sent out before they will have to return their answers early next year. However, what happens after that is the really interesting part.

The offers will be evaluated according to a stepped ladder of requirements, where all stages except the last one are of the go/no-go nature. If the preliminary bid doesn’t meet the requirements of a step it is back to go and the negotiation table (note, this is where the ‘preliminary’ comes into the process), and the Defence Forces will discuss with the manufacturer how their bid can be tuned to meet the requirements so that an updated bid can pass the step and move on to the top of the ladder. The goal is not to shake down the field, but to get the best possible offer from all five companies when it is time for the final and legally binding offers.

The first requirement is maintenance and security of supply. The supplier will have to present a plan for how the aircrafts are able to keep operating both during peacetime and in war. This will require plans for in-country spares and training for maintainers.

Moving on from here comes the life-cycle costs. The project is receiving a start-up sum of up to 10 Bn Euros, but after this is used up the operating costs of the system will have to be covered under the defence budget as it stands today. In other words, the cost of training pilots and ground crew, renewing weapon stocks, maintaining the aircrafts, refuelling – everything will have to be covered by a sum similar to that used for keeping the F/A-18C Hornets in the air. Naturally this ties in to the first requirement, as an aircraft requiring vast amounts of spares and maintenance will have a hard time meeting both the security of supply and the LCC requirements at the same time.

Industrial cooperation will then be the third step. 30% of the total acquisition value will have to be traded back into the country, as a way of making sure that the necessary know-how to maintain the aircrafts in wartime is found domestically (and as such this requirement ties into the two earlier requirements). Notably, current sets of rules require that the industrial cooperation is indeed cooperation directly related to the HX-program. Sponsoring tours of symphonic orchestras might buy you brownie points, but not industrial cooperation.

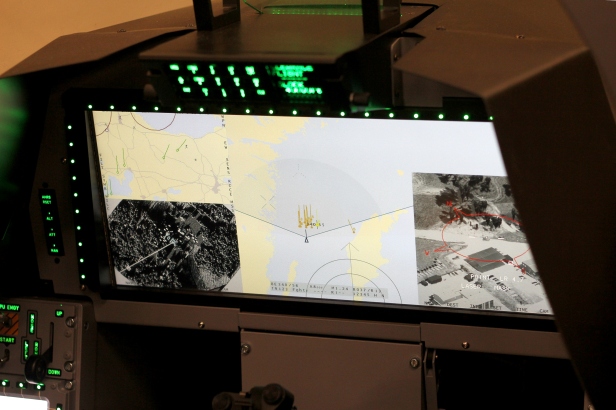

Following these go/no-go criterias comes wartime performance. This is the only requirement which will be graded. The Defence Forces will run a number of simulations of how the aircraft would perform in different missions and scenarios, gather information from the field, and possibly do flight trials. All of this will then come together to give a picture of how a given aircraft would perform as part of the greater Finnish Defence Forces in wartime.

Yes, wartime performance as part of the whole FDF is the sole factor that will rank the aircrafts in the acquisition proposal put forward to the MoD by the Finnish Defence Forces.

“But wait!” I hear you say. “Doesn’t economic considerations count for anything?”

Yes, indeed they do. Wartime performance require more than just 64 aircraft. If you can squeeze the price on the aircraft and its maintenance costs, the pilots will be able to receive more flight hours, and the Defence Forces will be able to stock more advanced weaponry (the low stocks of which is identified as a key issue in the latest Puolustusselonteko). Thus a cheaper aircraft allows the Defence Forces will provide more room for other things, which in the end make it more dangerous to the enemy.

Having received the acquisition proposal from the Defence Forces, the MoD takes over, and their job is to bring in the national security policy aspect into the equation. The national security evaluation coupled with the evaluation of wartime performance is then used to create the final acquisition proposal made by the MoD and put forward to the then government (i.e. the one which will take over following the next parliamentary elections). The final decision will then take place in 2021.

That the MoD will make a national security evaluation is interesting as it leaves room for politics overruling the wartime performance (though likely only to a certain extent). At first glance this would seem to favour the US contenders, however the situation might be more complex than that, thanks to the law of diminishing marginal utility. To what extent would a fighter deal actually deepen the already strong Finnish-US bilateral relations? There are already eleven confirmed export customers for the F-35, and a double-digit number of countries have bought into other US fighter programs as well, so would Finland’s inclusion (or absence) from that group be noticed in Washington? The US is also already Finland’s premier arms exporter (2015 numbers, unfortunately I didn’t find newer ones), and while this in parts comes from weapons for the Hornet-program, a number of other potential deals are on the horizon.

The Swedish offering has understandably not gathered quite the same number of export customers, but here as well even without a fighter deal the bilateral Finnish-Swedish cooperation is reaching levels that make one wonder whether significant improvements are possible? Geography and shared history also seems to dictate that the relation would survive Gripen failing to secure the HX order (though Charly might disagree). The benefits of operating the same aircraft is obvious when it comes to interoperability, but for political benefits it is doubtful how much 10 Bn (in the short term) actually would buy.

Enter France, a European powerhouse with an army still measured in divisions, a permanent seat at the UN security council, a nuclear strike force, a rather low threshold for military interventions, and a marked disinterest in what takes place on the northern shores of the Baltic Sea. The Finnish fighter order would be a big deal for Dassault, accounting for 40% of the total number of Rafale’s exported (96 firm orders to date plus 64 aircrafts for HX). It is also eye catching that a large percentage of the whole sum would go to France, compared to the larger amounts of foreign content in the Eurofighter Typhoon and the JAS 39E Gripen.

10 Bn Euros would not buy Finland a French expeditionary corps brimming with Leclercs in case of a Russian invasion. However, they just might ensure that Paris starts paying more attention to what happens in the European far north, courtesy of increased exchanges of people, experiences, and arms deals. If Finland would face an attack, having France as a political ally in Brussels and in the UNSC would be significant, even if the support would stop short of a military intervention. Another element is that as Washington is proving to be a more unreliable ally, the importance of the EU security cooperation is bound to increase (though granted from a low level to a somewhat less-low one), and with “the other European power” (Germany) showing limited appetite for anything resembling a confrontation with Russia over eastern Europe, the role of France in the greater Finnish security picture seems set to increase.

While Finnish security policy is famed for being slow in altering course and likely to favour trying to cash in further political points with Sweden or the USA, the question deserves to be asked:

Might it just be that we would gain more by having this investment go into our relationship with France?

Well said Corporal!

If we look at the export orders of the aircraft, remove all nations involved in the initial development:

Rafale Eurofighter Gripen FA-18 Superhornet

Egypt Austria (want to get rid of em) Czech RAAF

Qatar SA South Africa +7 if FA-18 is counted

India Oman Thai

Kuwait Hungary

Qatar Brazil

Gripen is one of the more successful fighters on the market.

If security guaranties are to be bought instead of a fighter the JSF or FA18 is the logical one.

and to make the list possible to read,

Rafale

Egypt

Qutar

India

Eurofighter

Austria (want to get rid of em)

SA

Oman

Kuwait

Qutar

Gripen

RAAF

South Africa

Thai

Hungary

(UK)

Brazil

FA-18 Superhornet

RAAF

+7 if A/B/C/D is included.

Corrections, JAS-39 has only been bought buy Thailand, Hungary and South Africa in low numbers. Czech Republic has leased few aircraft and the UK uses few as jet trainers. So far Brazil is only country that has ordered the new JAS-39E.

What are Super Hornet versions A/B/C/D? Or are you referring to Hornet versions A/B/C/D?

Super Hornet is a very different aircraft than Hornet. You can not put them into the same basket in any way except looks and saying that one is a derivative of the other.

Is F4F Wildcat the same fighter as F6F Hellcat?

I think 42 Rafales is enough. With the rest of the money we should buy Mig-35. Anyways we should have system that renews 1/3 of the about 100 planes total in a continuous cycle.

Well, I like Gripens too and we must remember Rafale and Typhoon developers announced new joint project for next generation plane. It might slow down the development of current Rafale too soon for Finland.